America Did Not Prepare for the Climate Crisis

The climate crisis is no longer “fast-approaching.” It’s here.

When my parents first bought their house in a small town outside of Seattle 10 years ago, they were shocked to learn the house had air conditioning installed. It was a neat feature, sure, but it didn’t matter much anyway — western Washington never gets hot enough to warrant using more than a big box fan.

10 years later, we ate our words. After two days of leaving it running, the air conditioning unit burned out from its sudden call to action. Seattle, a city known for its perpetual rain, suffered a record-breaking heat wave at the end of June. In the city’s 170 year history, it has recorded only three days at or above 100 degrees Fahrenheit. In one weekend this summer, Seattle surpassed this mark three times over three consecutive days.

“It’s crazy,” Emily Johnston, Communications Director at 350Seattle, told The Interlude in an email. “It’s not like a gear ratcheting up — it’s like the whole thing coming loose and unpredictable.”

This is part of a new, terrifying, life-changing normal throughout not only the Pacific Northwest, but the entire United States and across the globe. The effects of climate change are past “fast-approaching”; they are here. And the U.S. is vastly unprepared.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s sixth annual report, which was released August 9, found that humans have caused the planet to warm about 1.1 degrees Celsius since the 19th century. Should that number reach 1.5 degrees Celsius, the consequences will be far more dangerous, with billions of people experiencing life-threatening heat waves, floods, and droughts. What’s more: coral reefs, ice caps, and even some plant and animal species will vanish. By the end of the century, extreme sea level events could happen every year, when previously they had occurred once in 100 years.

The United States will not even see the worst of climate change. Around the world, climate change will hit island countries and poorer nations the hardest, such as Haiti or the Bahamas.

It comes as no surprise that the IPCC report looks grim. A 2017 study found just 100 companies account for 71 percent of global emissions, while CO2 emissions from households only contribute about 10 percent. Through PR campaigns and the emergence of “green products”, these companies have dumped an unrealistic sense of personal responsibility on individual consumers when it comes to fighting climate change.

And the clock is ticking: It’s possible for us to prevent further warming, and maybe even work to reverse the damage that’s been done.

A region known largely through associations like Twilight, Seattle is often depicted as cold, gray, and wet. Western Washington does see about 155 days of rain a year, which keeps the forests and vegetation green essentially year-round. Recently, though, it’s undeniable that not even the Evergreen State is untouchable when it comes to climate change. Increasingly hot summers have led to worsening fire seasons and a higher risk of drought. The recent heatwave (and the one projected for this weekend) was just the icing on top.

Despite its rainy reputation, Seattle is actually drier than most cities on the East Coast. Karin Bumbaco, the Assistant State Climatologist at the Office of the Washington State Climatologist Cooperative Institute for Climate, Ocean, and Ecosystem Studies (or CICOES), explained that even though western Washington sees more days of rain on average, the amount of rainfall in total is less than you’d expect.

“There’s really not a lot of rain in the summer,” Bumbaco said. The snow that collects on mountaintops during the fall and winter (called snowpack) melts in spring and summer, running into streams and rivers, and is used as water supply during the dry season. “So that’s why we have such a booming agricultural region east of the Cascades in the Yakima Basin, because they will have the reservoirs…but also the snowpack stores that water for use during the dry season for agriculture.”

“But we’ve been so dry,” she continued, “and then this heat event on top of the dryness has really exacerbated some of the drought conditions that we’re seeing in eastern Washington.” As it’s been dry, Bumbaco said the “dryland agriculture has really been struggling. They’re the ones that they’re not irrigated. So they’re not using water from the mountains. They rely on what falls from the sky.”

In central and northern Washington, lower soil moistures and more dead trees make easy wildfire fuel, sparked by campfires, fireworks, or cigarettes. In the west, rivers and streams may dry up faster and make it harder for salmon, a keystone of the PNW ecosystem, to survive.

The environmental effects of global warming have become increasingly transparent here, as it has all over the globe. Fires have left yet another season of the Evergreen State gray. Last year, the area was engulfed in smoke for weeks due to wildfires. Authorities cautioned residents to stay inside as winds brought up smoke from Oregon wildfires that made the air hazardous to breathe. This year, the Bootleg fire has become the third-largest fire in the state’s history, and has even created its own weather.

Now, after the worst of the boiling temperatures have passed, it remains warm in western Washington. Maybe not warm enough to prompt people to sleep underneath a damp towel, but warm enough to be uncomfortably reminded that climate change isn’t something to worry about for future generations. It’s something to worry about now.

Bumbaco said she felt “disbelief” at the heat wave.

“Even though I work in this field, and have studied heatwaves for several years now, [I was] just surprised,” she said. “I mean, still surprised that it was this warm so soon, into what we have been calling our future.”

Despite the shock, Bumbaco still chooses to feel “hopeful” in terms of slowing the ravaging effects of climate change on the region. She thinks “if the right policies are put in place, we can reduce our greenhouse gas emissions globally and get back on track to a more what we would call normal climate in the future.”

Christopher Mejia, a comedian whose TikTok about the PNW heatwave went viral, is worried about what climate change will mean for future generations. Even though his viral TikTok was funny (it was so hot, Mejia said, that Seattle’s infrastructure was planned “by a drunk toddler playing SimCity on hard” and that “I have so much sweat on my chest that a babbling brook is forming”), the anxiety he has for the coming years is serious.

“The world we’re giving them is like passing down your son your Toyota Camry that has 100 miles left before it spontaneously combusts,” he wrote in an email. “I feel helpless.”

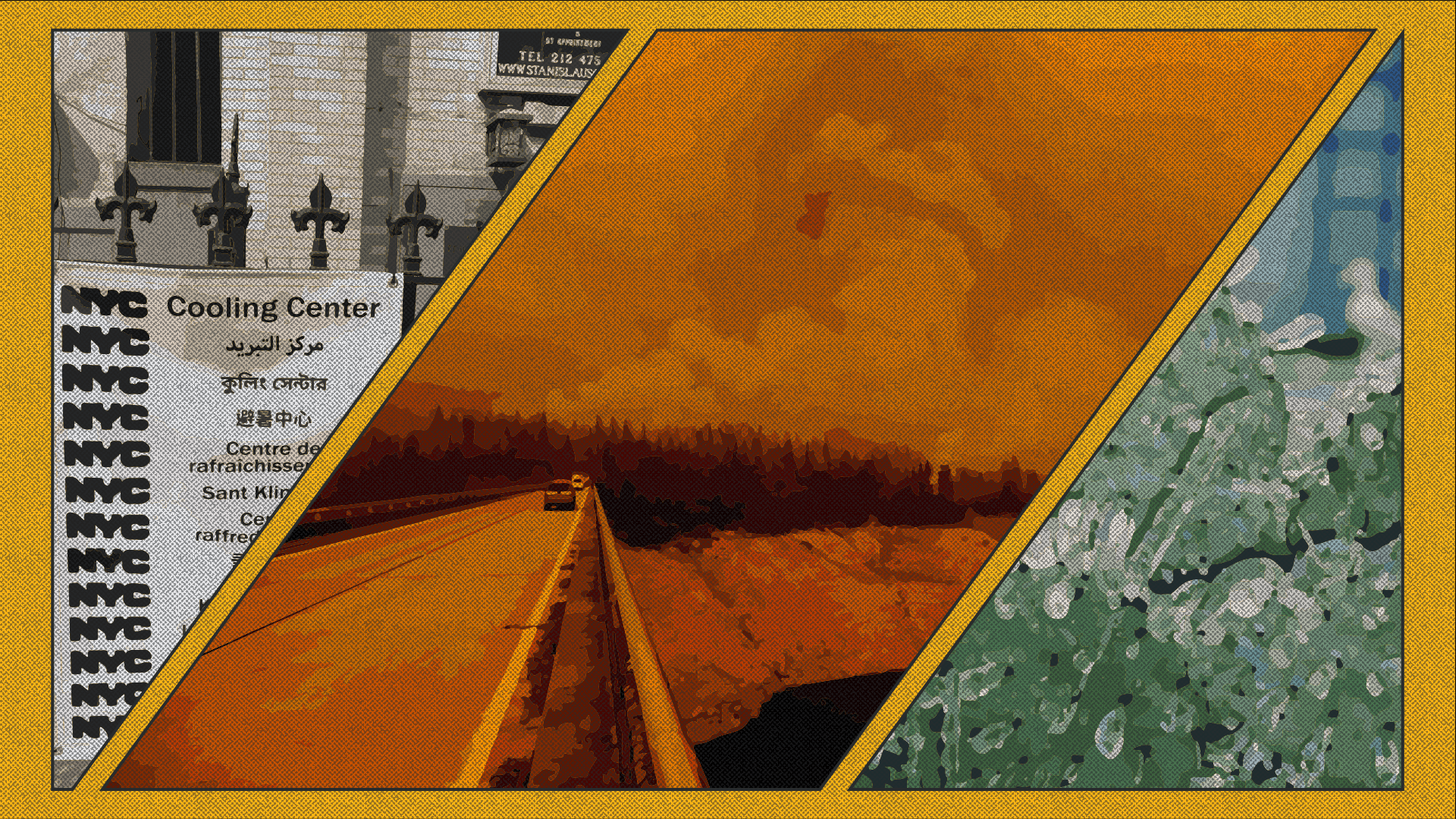

Temperatures above 100 degrees Fahrenheit are dangerous, especially for vulnerable groups such as unhoused people, lower-income people, and BIPOC communities. These groups are less likely to have AC in their houses or, as Johnston noted, to have access to greenspaces, parks, and beaches.

New York City faced similarly high temperatures not long after the PNW heatwave, followed by heavy rains from Tropical Storm Elsa that flooded subway stations. Southern parts of the country have also taken their fair share of battering this year: Nearly 200 people died of causes related to the cold when Texas was hit with a massive winter storm this February, while thousands of other Texans saw massive power outages, burst pipes, and more. Texas’ reliance on its own power grid (which keeps the state from needing to follow federal regulations) exacerbated the effects of the recent winter storm. As the extreme weather conditions worsened, the grid was unable to withstand the cold, and Texans had nowhere else to turn to when they lost heat and electricity.

The common thread: a lack of necessary infrastructure installation. Even though every dollar spent saves $6 worth of future damage repair, plans to mitigate climate change are slow on the uptake. While politicians hammer out how much money they’re willing to invest on the planet’s ecological future, the world is changing before our eyes.

And the climate crisis will not deal out a fair hand. The rich get rich and the poor get poorer. Throughout the floods, fires, freezes, and fevers, the wealthy are more likely to stay comfortable, as they can afford homes with AC, heating, and, most importantly, the ability to flee (looking at you, Bezos).

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed when you’re enduring the effects of climate change firsthand, rather than reading about polar bears thousands of miles away. In fact, climate despair is normal when the news about global warming is consistently bad news. But just because it feels bleak does not mean that the end of the world is hurtling at us with no way of stopping it.

This is where we are less powerless than we may feel. We can, for instance, pressure our local officials, senators, and House representatives, urging them to move forward with the Green New Deal, or a federal clean electricity standard (which was left out of the new infrastructure bill), or to invest in making public transportation more widely available. We can also contribute to mutual aid groups and help those hit the hardest by these climate disasters.

Already, the stress for climate mitigation is creating change. The $1 trillion infrastructure deal, which passed yesterday in the Senate with a near-bipartisan 69-30 vote, is a sign change is possible. Though some initiatives were left out from the original proposal (including clean energy tax credits) or cut back, the newly-passed bill includes a very necessary $21 billion for environmental remediation projects, $73 billion for electric grids and power structures, and $55 billion for water systems and infrastructures. These are major steps in the right direction.

In Washington State, like many others who are rapidly facing the effects of climate change, the infrastructure bill couldn’t be more beneficial. With Senators Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell at the helm, the state is slated to receive billions of dollars to help mitigate global warming and upgrade infrastructure, including improving water storage, giving money to the Sound Transit system, and measures focused on salmon recovery.

In the Pacific Northwest, the worst of the heatwave is over (for now, at least). While it’s cooled off, it’s time to turn the heat up on those who have the power to make meaningful progress against global disaster.

“If we have any care for anything, we have to do all that we can, right now,” 350Seattle’s Johnston wrote. She said she’s inspired by the hope that we still have time to make a better world.

“That’s what keeps me going even when things seem bleak,” she wrote. “That and the fact that I don’t want the evil, lying bastards in the fossil fuel industry to ‘win’ and destroy all that we care about in the process.”