The Pandemic Made Me a Housewife

Learning the true cost of domestic labor made me realize I’m not cut out to be a homemaker.

If you told me a year ago that at 22, I’d be fresh out of virtual college, unemployed, making dinner every night and folding a man’s underwear for him, I would have had a good laugh. But it’s not as funny when it’s reality.

When the pandemic hit New York City in early March, I was in my last semester of undergrad, about to graduate with a journalism and English literature degree from NYU. I had a lease with two roommates that was expected to last through the summer, an amazing university job that was supposed to be guaranteed until late August, and plans to apply for full-time jobs and culinary schools through summer.

As if the circumstances weren’t already terrible, in May, everything in my life fully went to shit. The pandemic was in a full, angry rage, and it did not care about my senior year of college. I presented my thesis project via a Zoom call and I watched my graduation “virtual tribute” on a laptop the day I was supposed to be throwing my graduation cap in the air at Yankee Stadium. I was laid off from my beloved NYU job. Then, the day after “graduation,” my roommates aggressively demanded that I move out of the apartment so that they could break the lease. I had less than a week to find a new place to live, and I couldn’t just fly back to my home state like everyone else was doing (thanks to my compromised immune system).

So, after my partner and I found a new apartment and moved all of our shit out to Brooklyn, we started a new quarantine life. He worked from home every day, and took full command of the desk I once used to sit at to write critical theory essays and complete Spanish homework. I started to become resentful towards my partner’s situation. A year ahead of me, he graduated from college with a normal ceremony, had the summer to work a part-time job and fool around at bars with his friends. He worked fellowships in the fall, and soon after, acquired a full-time salaried journalism job at a huge company making very good money. I had just graduated with the same degree, a resume full of internships and job experience, but into a failing economy and a job market that had lost over 20.5 million jobs as the unemployment rate jumped to 14.7%. With no schoolwork to complete and no job to occupy my time, I turned completely domestic.

As an impressively skilled home-cook and an obsessive cleaner, I used to joke that my ideal job was to be a housewife. Cooking and cleaning are both in my blood; the Mexican women in my family had drilled both skills into me from an early age. What could be a better job than to have no job, other than keeping the house in order? I loved to cook, and I kept my space spotless most of the time, anyway.

I thought that there wouldn’t be much else to do apart from basic cooking, cleaning, and the occasional gardening as a fun quarantine hobby. It turns out, domestic work requires a million micro-tasks — like organizing the fridge, straightening up the living room, and making the bed — that, at the end of the day, made me feel simultaneously like nothing had gotten done, and that I had just done a full day of unpaid work.

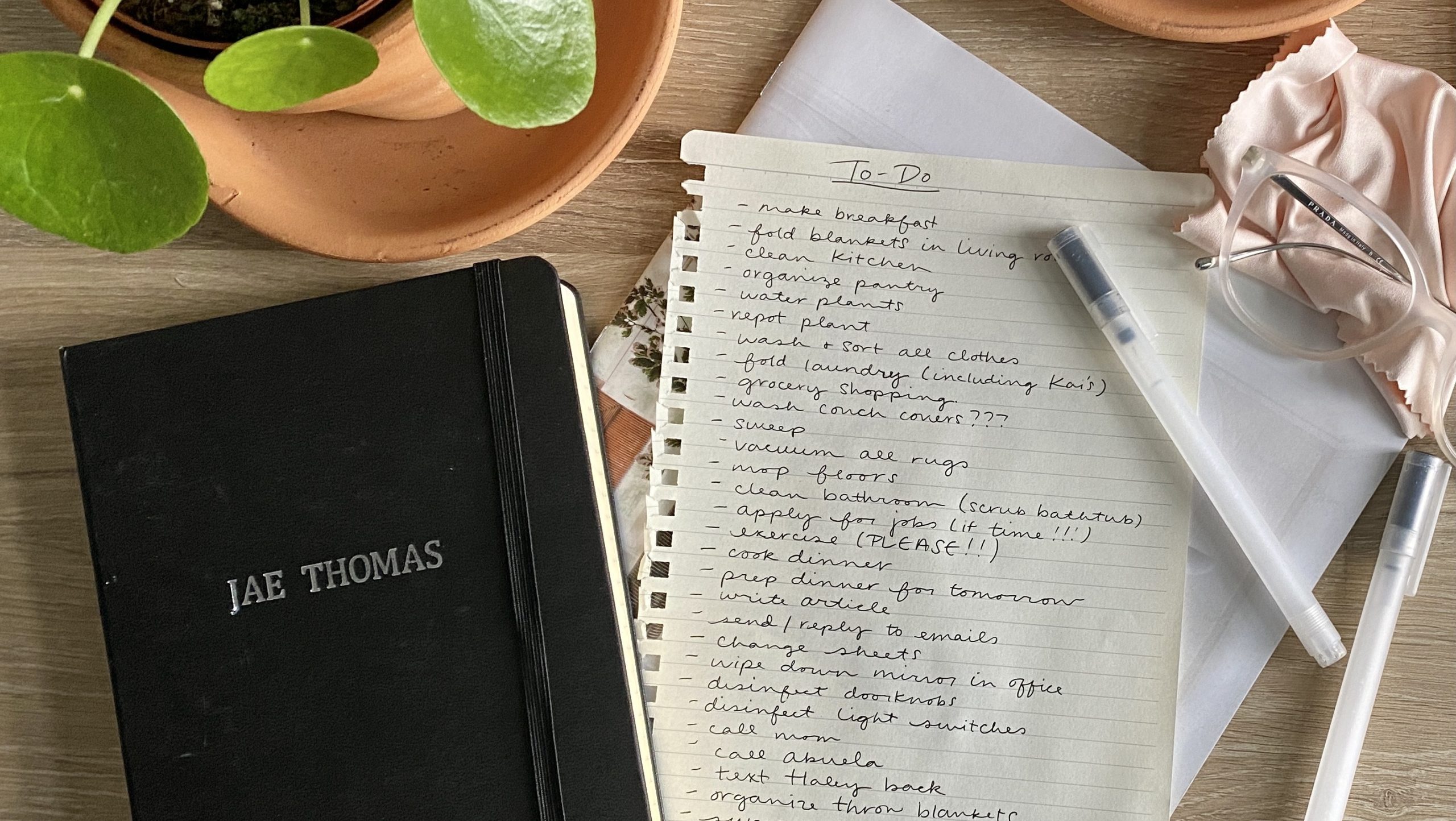

Almost every day, I managed to not sit down:

9:30 a.m. — Wake up and check email for any job interview offers.

10 a.m. — Make bed and tidy up the bedroom, living room and kitchen.

10:30 a.m. — Cook breakfast for my partner.

11 a.m. — Eat breakfast.

11:30 a.m. — Clean kitchen.

12 p.m. — Check/water all the plants I’ve acquired since the start of quarantine.

12:30 p.m. — Do laundry.

2:30 p.m. — Fold clothes (including, but not limited to my partner’s underwear).

3 p.m. — Go grocery shopping.

4 p.m. — Apply for jobs or write articles (alternating days).

5:30 p.m. — Exercise.

6 p.m.— Shower.

6:30 p.m. — Cook dinner.

8 p.m. — Eat dinner.

8:30 p.m. — Clean kitchen (again).

9 p.m. — Watch TV.

11 p.m. — Sleep.

It was the small tasks throughout the day that I completed between the scheduled chores like laundry and grocery shopping that seemed to drain me the most. Things like folding throw blankets that my partner and I used the night before, or dusting all shelves in the apartment frequently took up more time than I would have liked them to — both in practice and just thinking about them. The checklist in my brain got progressively fuller and fuller, never allowing me to relax or take any downtime until the full list was checked off at the end of the day. I would not, and could not, leave anything until tomorrow — and if I did, it would eat me up.

Though the apartment is perpetually clean and there are almost always elaborate dishes on the table at dinnertime, it turns out that I’m not exactly cut out for domestic labor. Every night when I got in bed, I felt equal parts unproductive and exhausted from all the things I had done. I had been raised to be independent and mostly unreliant on others, but without a job and especially after the extra $600 per week unemployment payments ended, I felt like I was relying more and more on my partner’s income. It made me feel weak, but worse, it made me feel dependent on him. He was suddenly paying for groceries and take-out meals that we used to split the cost of. He bought things for the apartment that I couldn’t afford myself. It seemed like he felt bad — that I was at such a shit point in my life — and wanted to pay to make it easier for me. After all, he had a stable income and I didn’t.

With little to do but housework, my entire identity slowly became all cooking and cleaning. Conversations with my partner centered around home-decor that I liked and meals that I would make for dinner that week. With no friends to see, very few people to talk to on a regular basis, and virtually no job interviews offered to me, I got stuck in a loop of believing that my self-worth was tied only to things that I could do for money. It didn’t matter that I was putting lavish meals on the table every night, or that I started a passion project of writing about my family’s recipes, because I was virtually alone and seemingly unemployable.

It took this experience to realize that domestic labor isn’t easy, and being a housewife is not the cushy lifestyle I thought it would be. I come from a working family, where none of the women had (what I thought was) the luxury to stay at home to raise children and take care of a household. My mom, a single mother, always worked full time, then came home and made dinner for us. It’s clear to me now though, that part of the labor of homemaking is holding on to a sense of self. It’s the best (or worst, in my case) exercise in not allowing your job to define you, and remaining self-realized through a day full of tiny tasks that seem insignificant but still need to be done.

Thankfully, I have a job now, and my little chores seem less important than they did when they were my whole purpose. Maybe it’s that I have less time to worry about things like taking the trash out or organizing the pantry, but I’ve come to terms that everything will never be completely finished. Even when it was my whole purpose to clean and organize and cook everything, I couldn’t do it all. There will always be more little things to do tomorrow, or the next day, and I’m better off without trying to do them every day. Now, I can gladly skip the vacuuming, or leave the bed a mess for one day, but, come the weekend, everything on the checklist must be crossed off.