Even Animal Crossing Can’t Save Me

No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t separate my real self from my game self.

The other day, my villager Blaire turned to me and said, “I do hope Lilac Cove life is everything you’d hoped for.” Blaire, a snooty squirrel villager, was the first resident of Lilac Cove to gift me her photo — the ultimate indicator of friendship on Animal Crossing. The moment she uttered those words to me, I felt a sort of kinship that transcended the game. I’m not alone in this thought; many players have shared intimate moments they experienced on their islands, like receiving an almost too on-the-nose note from a villager after a break-up or a gift from “Mom” near the anniversary of a player’s mother’s death.

Blaire just shattering my little heart.

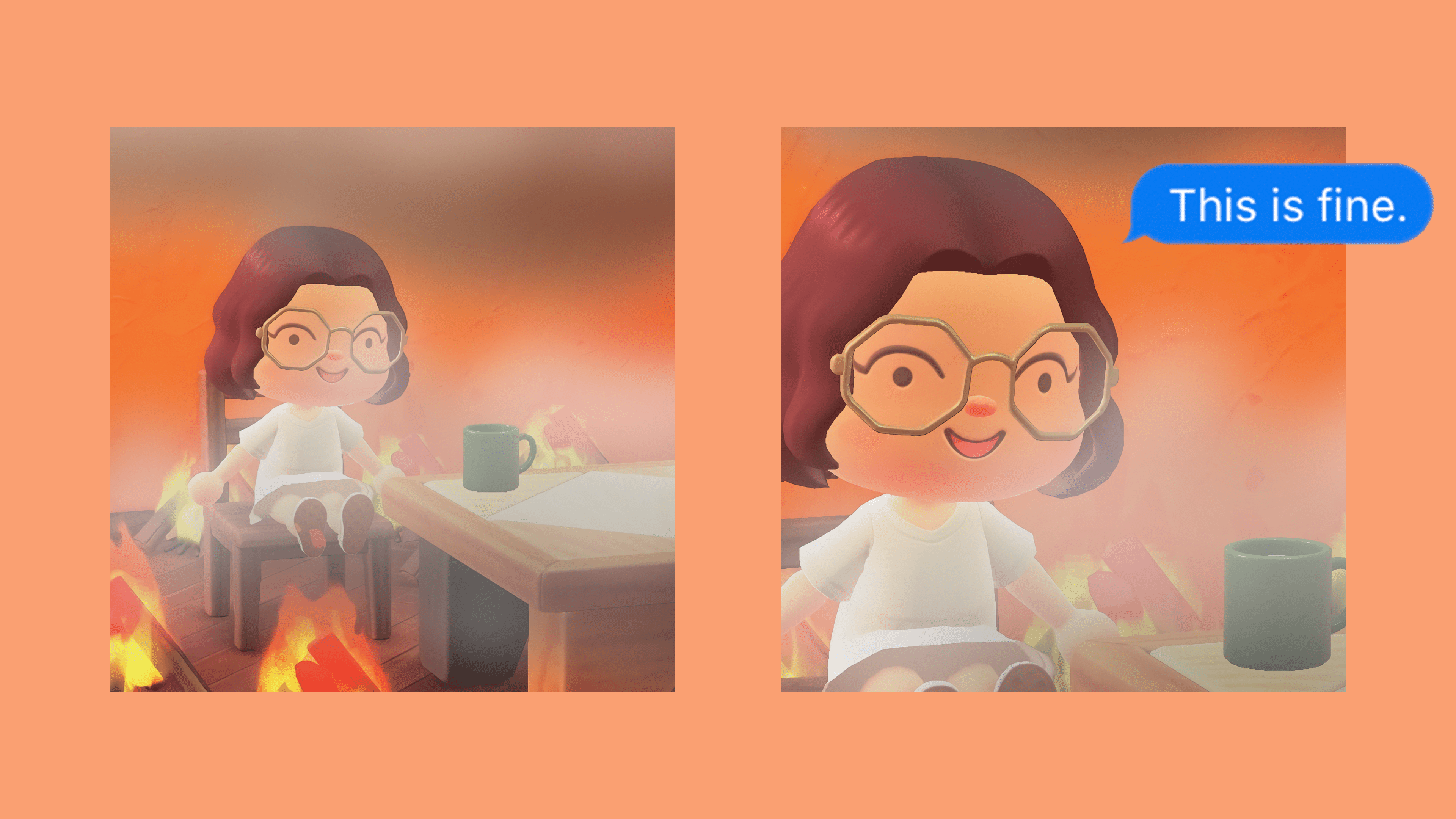

When I created Lilac Cove in June, I expected to manifest a haven, one where I could be myself. The first design I made was a bi flag for my island. I wanted Lilac Cove to be the place I always dreamed of: by the water, where I could dress the way I want and express myself comfortably and exuberantly. Every morning I would make myself an iced coffee (in the real world) and sit outside for 15 minutes to play. The game became my little solace in a period of turmoil, frustration, and monotony. I imagined Animal Crossing would offer me an opportunity to escape the feelings that derived from this period, but I’d soon discover that my mentality in my everyday life couldn’t be set aside, even during a game.

After my university went remote in March, I decided I would wait until I completed my senior thesis to purchase the console and reward myself for my hard work and self-control (something I have little of). By May, all Switch consoles were sold out and I spent my last days of college refreshing Best Buy’s page. In mid-June, for my 23rd birthday, my boyfriend surprised me with both the game and Switch Lite console. We had been separated for four months at that point due to the pandemic, and this was a little piece of him, oddly enough, I could hold.

Photo my boyfriend took of me on my birthday.

I played obsessively for the first month, switching between the console and watching television. Just as the country felt like it was falling apart, my world — Lilac Cove — was just building. When I would walk around with no make-up on, still in pajamas, I could escape to a place where I had blue hair and wore a “dreamy dress,” and a hot pink cowgirl hat. I’d spend my days there fishing, wishing I felt like I existed outside of this game. It wasn’t until I unlocked terraforming that the island given to me would feel less like my own and more like a creation I had to execute, proving I could create something great and so imaginable with the “hard” work of my two thumbs.

Living my pride out-loud on Lilac Cove.

I started watching Animal Crossing Five Star Island videos on YouTube and became an avid lurker on the Animal Crossing subreddit. I saw islands worth marveling over and the same seven cute villagers featured on my screens. I bought amiibo cards for villagers I saw strangers boast about online. I invited Peanut and Julian onto my island — kicking out my villagers in the process. The more I turned to the internet for inspiration, the less the game became about the fun I was having, and more about the expectations I set for myself because I began comparing my island and my experience to others.

In the real world, I struggled with my confidence. Four months after graduation, I was still unemployed, living at home, and completely losing my sense of self. I looked on LinkedIn, on Twitter, and even on Instagram seeing everyone around me share their accomplishments, their job announcements, or the benefits of fulfilling new hobbies. In a pandemic that left me feeling isolated and insecure, I started to doubt my self-worth. It seemed everyone around me was able to “make” something of this period. The longer I was stuck in my family home, away from my boyfriend of three years and friends from college, still getting ghosted by employers, the more I played Animal Crossing. The game that was built to play just a few minutes or an hour every day became an incessant habit to fill the void I knew existed, but couldn’t acknowledge.

I started time traveling, ravishing any sense of “new-ness” in the game. I exchanged my villager, Raymond, for 50 Nook Miles to experience “Dreamy Hunting,” the process of hopping islands to find your “dream” villagers. I spent an entire evening looking for my “dream” villagers, probably around four or five hours. In the end I spent all my miles and settled on a cute little rhino villager because I was so drained and worn down from the process.

The game became less about relaxation and wonder, and more about bleeding the game dry in its escapist value. I would manipulate the game to satisfy my needs once my desires were left unsatisfied, and my expectations changed.

In early August, around the time I would go to Lake Placid with my family every summer, I decided Lilac Cove would become less of a beach haven, and more of a cottage-core, cozy, mountainous lake town. I spent hours crafting the terrain “by hand,” carving a heart lake in front of my newly placed home. I’d spent hundreds of thousands of bells to move my villagers’ homes around this lake.

Now, when I walk around it, I’m reminded of what all this game evolved into for me. I let the external opinions online and my real life seep into the game in a way that became the epitome of what our lives truly are like: deeply influenced by each other and the expectations we set for ourselves. When I walk around my village, I feel too tired to change it. Just like in my everyday life, I am now often too tired, maybe even too depressed to do the things that would make me happy. Lilac Cove embodies all of my worst dreams — one of monotony.

I’ll still mosey around Lilac Cove, buying cute clothes and enjoying new updates, but until I gain the energy to destroy and rebuild my island, I’ll remain stuck in the world I’m left with on my Switch and in my real life: one that’s still beautiful, but pretty much the same every day.