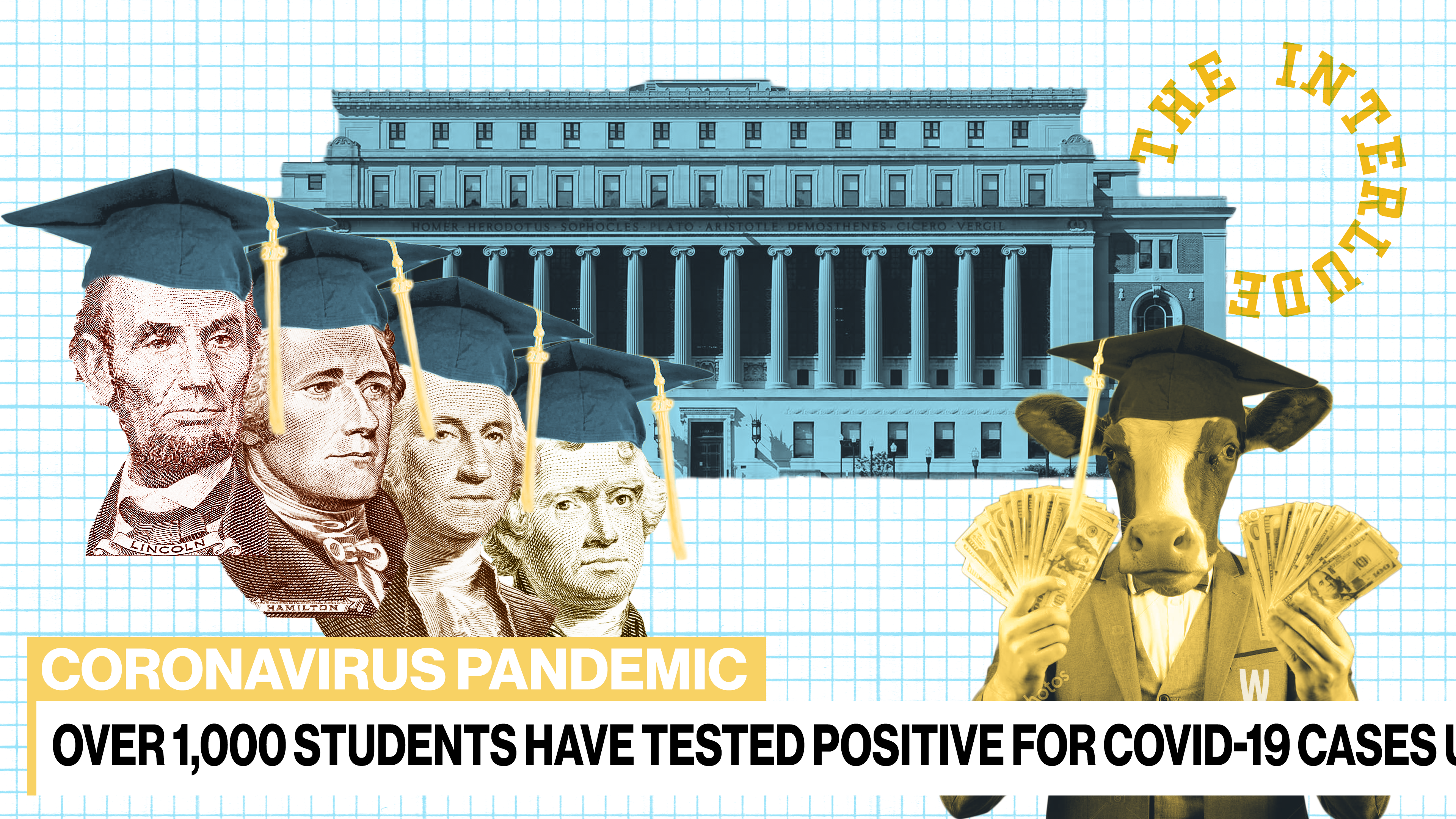

The Back to School Money Grab

Universities around the country show a blatant disregard for students’ lives, while collecting tuition — often at full price.

As young adults flock to colleges and universities around the country, it has become increasingly clear that for some universities, the safety of students and employees is a secondary concern to financial comfort. Given the emergence of campus COVID-19 outbreaks across the country, coupled with lethargic or nonexistent responses to complications from bringing students back to campus, it’s clear that U.S. institutions see their students as expendable cash cows.

The coronavirus pandemic upended the look and feel of classroom learning all the way back in March, forcing schools around the country to rapidly adapt curriculum and guidance for in-person, hybrid, and online learning. But now, as schools reopen and campus COVID cases top 26,000, an increasing number of reopening plans are falling apart. Just a week after moving students back on to campus, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill announced an outbreak of four COVID-19 clusters and moved undergraduate learning online. Shortly after, the University of Notre Dame and Michigan State University followed suit. (Notre Dame said classes would be online for the two weeks; Michigan State did so for the remainder of the year.) New York University made headlines for providing quarantine students with insufficient meals, or in some cases, no meals at all. The blunder ended up costing the university a pretty penny; NYU had to provide students $30 per day for dinner delivery, all because the university hired a company with a history of giving vulnerable children spoiled food instead of taking the time to make sure proper nutrition would be delivered to students stuck inside their city dwellings.

While the pandemic chipped away at budgets at institutions across the U.S., a larger issue of university cash flow has been mounting for years. American higher education programs have increasingly relied on tuition money to operate. In 2017, more than half of U.S. states relied more on tuition revenue than public funds, according to the Association of American Colleges & Universities. For the 2018–2019 school year, nearly 50% of the University of California’s projected revenue increase came from student tuition and fees. Private institutions haven’t fared much better. Twenty percent of Harvard University’s 2019 revenues came from tuition; 43% came from philanthropic gifts. Fifty-seven percent of New York University’s 2019 operating budget relied on student tuition and fees; another 10% came from housing and dining. When colleges shut down in the spring, many colleges pro-rated or returned some housing and meal plan fees, but clung to tuition dollars while they invested millions in online learning. In April, Moody’s Investors Service predicted that returning to in-person classes would make impacts on budgets “more manageable,” especially if international students continued to pay tuition. It appears institutions took note. Institutions seem more willing to risk the health of students and staff to make ends meet. But with fewer resources, a fledgling public health infrastructure, and a rush to secure tuition, preventing the spread of a deadly virus has proven to be near impossible. Chapman University’s president told the New York Times that the school spent $20 million prepping the campus technology and public health. He estimated that moving school fully online would cost the university another $110 million. The move, coupled with a lack of state and federal aid, put even the most well-off institutions, like UNC, in an uncomfortable financial position. For public universities and small private colleges, the pandemic has proven to be financially disastrous.

But for families, many of whom struggled financially during the economic crash fueled by the pandemic, sending students back to a lackluster educational experience at full price may be more disastrous. Parents and students across the country have voiced concerns about the cost of a college education in the middle of a pandemic, arguing that paying full price or increased tuition for online learning isn’t worth the cost. More than 1,100 petitions calling for tuition refunds have been posted on Change.org. Some students who can afford to take a gap year have elected to do so instead of paying for online schooling. Twenty percent of Harvard’s incoming class deferred enrollment. And already, parents have sued schools including George Washington University, the University of Connecticut, and Miami University over discrepancies in online learning quality. Perhaps more pressing than the fate of universities moving to online schooling, is the safety of students at schools where reopening for in-person learning was the top priority.

As campuses continue to reopen, concern has grown over universities’ ability to control potential sources of outbreaks both on and off campus. Texas A&M University had more than 690 positive cases in the first three weeks of school. The University of Alabama has more than 1,000 cases only two weeks into classes. And the University of Southern California has 104 cases in what is being qualified as an “‘alarming’ surge” by on-campus media. Even when universities have quarantine protocols that limit time outdoors and interacting with others, and promote hand hygiene and mask wearing, students have found ways to defy them. Videos of Syracuse University students ignoring social distancing and quarantine protocols went viral. Photos circulated of Greek fraternity and sorority parties at University of Georgia, despite reports that a university employee died from COVID-19 just a few weeks before. Georgia Tech also has COVID-19 clusters linked to Greek life. And the University of Miami has more than 180 confirmed COVID-19 cases, even though the university has suspended students for violating campus safety rules.

The number of reported cases (with more likely to come) and rolling closures, is cause for concern. The safety of students and staff appears to be declining in the few weeks campuses have been open. But the conflict between university messaging and the safety concerns paint a much darker picture: students and staff are sounding the alarm, but universities turning a blind eye.

On July 1, a Yale professor told students in an email that they “should all be emotionally prepared for widespread infections — and possibly deaths.” The email, obtained by the Yale Daily News, also told students they should “emotionally prepare for the fact that [their] residential college life will look more like a hospital unit than a residential college.”

It is unclear whether the professor’s intent was to encourage students to stay home, or to comply with campus safety protocols. Clearly, enough was amiss that a psychology processor felt the need to tell students to brace for death. Regardless of whether the university approved the communication, the fact that such an email was sent to students with no apparent reconsideration of student safety shows just how little Yale cares about the safety of its students when it could be making money from student housing.

But students at some of the already-affected schools said that they have been sounding the alarm for months about their universities’ ability to keep students and staff safe. A student at the University of Texas recently took to Twitter to complain about the university’s response after serving on a reopening committee alongside administration. “We asked UT admin to invest in preventative measures for COVID — free face masks, universal COVID testing, free PPE for staff,” Vinit Shah wrote on, “They refused.”

In a follow-up post, Shah encouraged students to re-think their plans to return to campus and alleged that UT’s administration’s first priority was profit — not student safety.

It took viral TikTok videos for NYU to feed quarantined students more than a bottle of water and watermelon chicken salads.

@onetoomanytwizzlersok but can somebody tell me what watermelon chicken salad tastes like? #nyu #nyufood #nyutiktok #watermelonchickensalad #fyp

Universities’ response to criticism has been lackluster at best. NYU released a Twitter statement that placed blame on its vendor, Chartwells. And in a decidedly immature move, Purdue University published a list of “compliance naysayers,” with quotes from news articles and experts questioning the university’s readiness and ability to prevent an outbreak. This public mocking over legitimate concerns for student safety demonstrates an unwillingness to prioritize students over profit. (Sorry, President Daniels, you’ll have to add The Interlude to that list.)

Ranging from negligence to apparent malice, it has become increasingly clear that students at universities across the nation cannot depend on their schools to keep students and staff safe. The decision to bring students back without proper planning or contingency measures shows just how much universities anticipated they would need students to return in order to sustain themselves.

But it didn’t have to be this way.

Harvard decided in July that it would move undergraduate courses online. The University of Pennsylvania also decided to hold classes online. And despite making a last-minute change that left some students who came to New York City early scrambling, Columbia called off its in-person undergraduate classes two weeks before the semester was scheduled to start (although after some out-of-state students moved to New York to quarantine.) The university reduced fees and returned room and board for students forced to take classes from home. But these educational institutions have a brand value that may sway students to stick around, even when the education is online.

Without a bailout package to help schools stay afloat or federal oversight of campus reopenings, students will continue to be bled dry for tuition money, whether online education is on par with in-person learning or not. What has become increasingly clear is that for many universities, the safety of students and employees is a secondary concern to financial comfort. And the ramifications of that choice are deadly.

With more than 26,000 COVID-19 cases, it’s only a matter of time before students and staff die from infections they contracted on campus. If the national death rate holds for college students and the older adults they interact with as the U.S. gears up for a second wave of virus outbreaks, we can expect to see at least 700 deaths resulting from reopening college campuses. (And that is not counting the tertiary community spread that could occur by sending students home after they test positive.)

Since universities don’t seem to care much for student health, perhaps they will take note of the liability posed by deaths on campus. While it’s unknown how the courts will determine what universities’ obligations are to protect the health of its employees and patrons, lawsuits are bound to result from deaths related to campus COVID-19 exposure. If current budget constraints were a concern, having to pay millions in settlements to families of dead students and staff could tank the healthiest of university budgets. Not to mention the emotional damages students and staff may be entitled to after enduring such a traumatizing school year. After all, it’s hard to squeeze money from your cash cows when they become skewered beef.