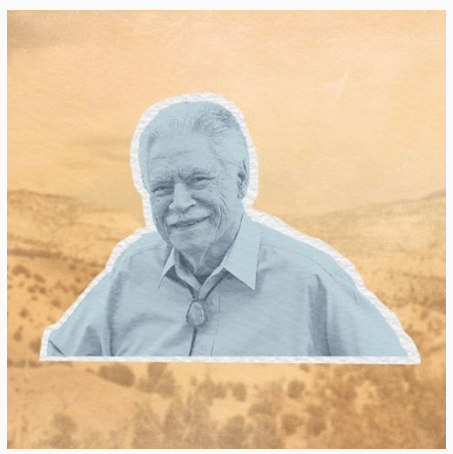

Prolific Chicano Writer Rudolfo Anaya Dies at 82

The novelist and educator gave voice to Latinos in the American Southwest.

Rudolfo Anaya — the pioneering Chicano writer best known for his 1972 novel Bless Me, Ultima—died of an undisclosed cause at his home in New Mexico on Sunday after a long illness, his niece told the Associated Press. He was 82.

Anaya helped to spearhead the Chicano Literature Movement in the 1970s. His first novel, Bless Me, Ultima came at the height of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, a time of self-determination for Latinos across the country, especially those of Mexican descent. College student activists in particular demanded resource equality and more Latino writers included in university curriculums. Anaya, along with writers such as Tomas Rivera, Rolando Hinojosa, and Miguel Mendez helped lay the foundation for contemporary Chicano Studies.

Bless Me, Ultima is a spiritual narrative rooted in Chicano and Southwestern folklore about a young Mexican boy in post-World War II New Mexico who develops a relationship with a curandera, or spiritual healer. The novel generated great acclaim in the Chicano community, and Anaya was soon designated “The Godfather of Chicano Literature.”

Anaya was born in 1937 in the small village of Pastura, N.M. and was delivered by a local curandera. He was the eighth of 10 children, all of whom learned Spanish as a first language, in an area at the intersection of Spanish colonization, Mexican culture and indigenous spirituality. His work would draw from this crossroads of cultures, giving voice to the modern Chicano community in a historical and spiritual context.

In a 2017 interview with New Mexico Magazine, Anaya said, “The heart of New Mexico is, for me, the people, la gente — los compadres, las comadres, los tíos, las tías, los vecinos. It’s the connection and the understanding between my Indo-Hispano cultures. If people don’t make that connection, they don’t understand New Mexico.”

Along with writing novels, short stories and a number of children’s books, Anaya worked tirelessly as an educator, first working as a high school English teacher in Albuquerque in the 1960s while pursuing his writing career, and later teaching classes at the University of New Mexico, starting the university’s creative writing program. He also set up a writer’s retreat in Jemez, N.M. for aspiring Latino writers.

Anaya received a National Humanities Medal in 2015 “for his pioneering stories of the American southwest.” He received numerous other honors, including the American Book Award, two National Endowment for the Arts literature fellowships, and the NEA National Medal of Arts Lifetime Honor in 2001, among others.

In a statement, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham said that Anaya’s work “truly captured what it means to be a New Mexican” and that “[h]is life’s work amounts to an incredible contribution to the great culture and fabric of our state.”