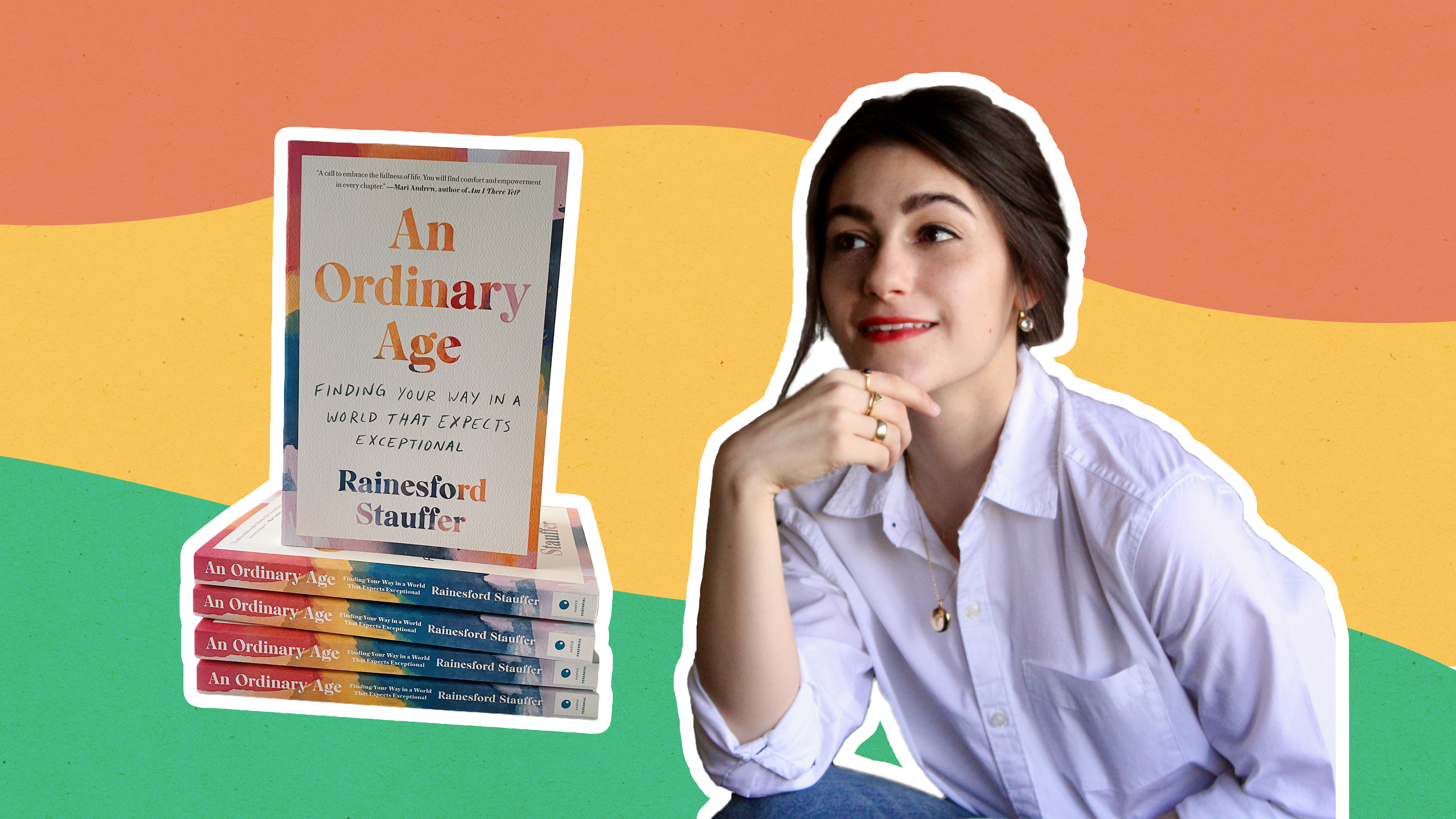

Rainesford Stauffer’s ‘An Ordinary Age’ Deconstructs Young Adulthood

What does it mean to come of age in the 21st century?

Young people often hear that college and their early 20s are the best years of their lives. But for many, financial insecurity and the lack of a robust social safety net make this a far-fetched reality. In Rainesford Stauffer’s new book, An Ordinary Age, the journalist-turned-author explores the pressure to lead an extraordinary life in spite of these hurdles.

Despite drastic changes to traditional markers of young adulthood, like graduating college, buying a house, and getting married, the insistence on reaching these milestones — and doing so effortlessly — remains intact. To highlight this, Stauffer interviewed dozens of young adults, including Lexi, who graduated with a job lined up only to find it cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic; Luna, who had to work a full-time and two part-time jobs for 80 hours a week to stay afloat; and Brie, a Black woman from the South Side of Chicago who never imagined buying her own house or having children because she wasn’t expected to “make it out.”

A Native Kentuckian, Stauffer has proven herself adept at capturing the current cultural moment and turning it into empathetic journalism, appearing in the New York Times, The Cut, Teen Vogue, Vox, and The Atlantic. As she spoke with more and more people, she began noticing a pattern: they all felt enormous stress to be the best version of themselves, even if that meant neglecting their physical and mental health. Stauffer casts light on the structures that perpetuate these feelings in her debut book, which debuted on May 4 from HarperCollins Publishers.

Stauffer spoke with The Interlude about An Ordinary Age, her own experiences, and the value of leaning into ordinariness.

As a young adult struggling to make do, working multiple jobs, and freelancing, your book resonated with me tremendously. I was so taken with it that while reading it tears were forming in my eyes and a man approached me to ask if I was okay. You touch on parts of young adulthood that are a reality for many. Firstly, what prompted you to write this book?

Well, now I’m going to start our interview by tearing up! So, much like you, I was presented with this narrative of young adulthood that was popularized through everything from our politics and higher education to coming of age pop culture stories of big adventures, finding yourself, and all the trials and tribulations that unfold. In my early 20s, I had dropped out of college after my freshman year. I went back and finished online while working a full-time job — didn’t feel like I could really get it together in the sense that I thought that I would.

There’s this assumption that if you’re lonely, that’s your problem, because you need to figure out how to make friends. And if you lose your job, that’s also your problem, because you should have been working harder. To me, it felt like no matter what, nothing could ever just be good enough, there always needed to be something that I was working toward. Then the further I got into my freelance career, I started noticing that when I was talking to sources — a lot of whom happened to fall into this age range — no matter the conversation, whether it was activism, climate, or school, somehow we always ended up talking about this undertone of ‘There’s something that I personally, as an individual, should have done better to make the most of my life.’

Then when I started researching, I realized it’s actually not that somehow every young adult is behind. What it actually means is that young adulthood has fundamentally changed. We’re really not grappling with what that looks like — on a national and international scale, but also just personally. It was those conversations that were the initial point of thinking ‘Oh, not only is it not just me, but there’s something bigger here at play.’

Throughout the book, you frequently relate the anxieties young adults experience to a culture of individualism, capitalism, marginalization, injustice, and oppression. While it is evident that all of these are interconnected, how do we collectively address these issues?

I think this is a phenomenal question. And it’s one I kept thinking about while I was reporting because at times it didn’t feel like the takeaway of the book was clean enough. We know what we need. We need affordable, quality education, living wages, and a sense of safety. We need to dismantle white supremacy. These things aren’t just going to go away. And they’re certainly not going to go away because we talk about ordinariness in a book. I tried to be very cognizant of the fact that it can’t just be our personal changes, we do have to push for a more equitable and just society.

At the same time, a lot of young people are left thinking ‘Well, what do I do in the meantime?’ The conclusion that I drew when I was talking to people is that we have to start talking about this a lot more. It has to be far less abstract. Right now, so many narratives about young adulthood are rooted first and foremost in the idea that every young adult is white and upper middle class. Not every young adult has that experience. The traditional sociological markers of adulthood have changed. I didn’t know that before I started reporting on this book and a lot of the sources I spoke to didn’t know either.

Why are we hiding the fact that so many components of our world have changed? Somehow we’re expecting young people [to be] the only ones who won’t change. That doesn’t make any sense. In addition to the policy component that has to exist, I think we have to listen to young people and not dismiss their experiences.

How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect how this project unfolded and your thinking about the themes you address in the book?

I submitted the full manuscript on March 1, 2020, a few days before everything shut down completely. It became obvious very quickly that this was not going to be a two-week thing. It was a lot of grief, mass death, and a lot of ramifications. Firstly, we were going to have to update the book because of the pandemic because anything that didn’t reference it was going to feel completely outdated. And secondly, it was how to keep the book from being a COVID-19 book because what we know is that these pressures existed before. But, I went back to a lot of sources to talk about how the pandemic has changed their lives and whether it has increased these pressures. The conversations really drove home for me how things aren’t going to get better just on a dime and things are actually going to get worse. For me, it was really important to make sure that the book showed that all these things existed before the coronavirus.

One of the most striking moments in your book for me personally was when you draw the comparison between growing up and grief. Could you please expand on that?

In young adulthood, there’s this idea that you need to get over things, and you need to get over them quickly. You need to bounce back, whatever that means. And what we’ve seen over the last year with mass deaths, failing governmental response, and continued systemic racism and police killings, is that these are not things that [will] leave us unaffected. There’s this trope of young adults as people that exist in a bubble until they grow up and enter the real world.

I think that that does a tremendous disservice to young adults who experienced grief prior to young adulthood and those who are navigating grief for the first time. There are so many different forms that grief takes: losing a parent, a partner, a family member, or a friend. But, there’s also this sense of grief about what life could’ve beenー mourning the life that you’d imagined for yourself. I do hope that this year transforms our relationship with grief and with our feelings in general. And this is especially true for workplaces and schools. This idea that we don’t bring what happens to us outside of the classroom or outside of the workplace into those spaces is misguided. Young adults can have a pivotal effect in changing that mentality.

You spoke to many young adults for this book. What did you discover or learn from the people you interviewed that was especially illuminating that you hadn’t necessarily thought about when you first started writing the book?

Oh, my gosh, so many things. I think that the broad strokes answer would be that young adults are complex and have various identities or circumstances they’re navigating that are all different from each other. I think that just what was so illuminating about those conversations was how often we have shared feelings that are obviously impacted by our circumstances that then play out in different ways. The breadth of experience was astounding. One example is my conversation with Brie, who I quote in the introduction. In our conversation, she describes listening to older people talking about their 20s and realizing she never imagined herself there. She never imagined herself making it that far into this version of adulthood. To hear her speak so candidly about coming of age in a society and circumstances that weren’t built for her was a gift. I’ll carry that with me for the rest of my life.

What would you like young adults to take away from your book?

What it means to be a young adult has changed. It’s not that you’re failing to meet milestones or markers of what it means to be a successful young person. It’s not you, it’s the circumstances. My hope is that someone walks away with this idea that your ordinary self and your ordinary feelings and your ordinary day-to-day existence is actually what is most formative about your life. We’re trained to recognize big moments and accomplishments like graduations, jobs, and pivotal relationship moments. And it’s not to discount those things. They’re definitely formative, too. But I think we really have a tendency to overlook how much we’re shaped by our own day-to-day impulses and curiosities. One of the greatest things you can do in young adulthood is give yourself space to focus on your ordinary self. Think about who you are and what you want your life to look like separate from all the noise of what you’re supposed to want.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. An Ordinary Age is out on May 4 and you can order it here.