52 Years Later, White Artists Are Still Exploiting Disco and Ball Culture

Popular artists, from Madonna to Jessie Ware, profit from Black and Latinx LGBTQ culture.

I stumbled onto Jessie Ware’s latest album “What’s Your Pleasure?” with glee this January. As a connoisseur of all things disco, I was transfixed by Ware’s electric voice and the sound she created. Her music transformed my bare living room into a sparkling dance floor reminiscent of the gay prom I attended in college. Suddenly, I wasn’t alone listening to Ware’s album through my headphones — I was dancing among my gay friends to the intensity and thrill of her songs.

For those 53 minutes, Ware’s music embodied the core purpose of disco: it reminded me of a moment when I felt most liberated and connected to other gay folks of color. But knowing the history of this genre complicates my admiration for Ware’s album, because it’s one more instance of a white artist profiting from something created by marginalized communities.

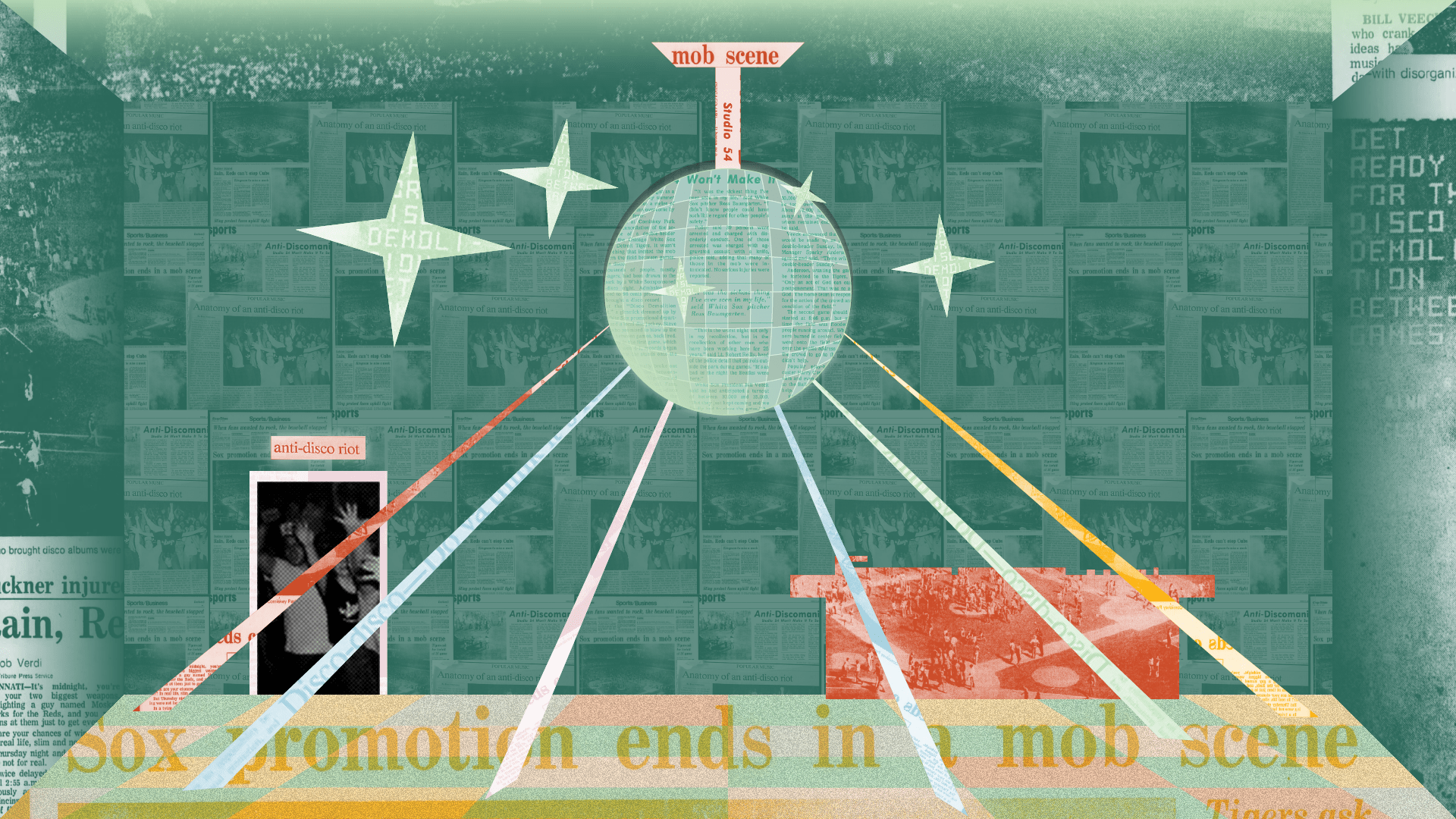

Disco emerged from Black (including Afro-Latinxs) and LGBTQ nightlife in New York City in the late 1960s. It was in clubs and on the dance floor where these communities could feel united with one another and authentically express themselves, historian Hadley Meares wrote for Aeon in 2017. But during its heyday, disco also received backlash from white people. Slogans and events were riddled with racism and anti-LGBTQ sentiments, like “Disco Sucks” and the Chicago White Sox’ infamous Disco Demolition Night.

I have a hard time reconciling my love for Ware’s album and my identity as a Latinx gay femme. I can see why she leaned into this genre of music. It’s fun and euphoric and engulfs every part of you in a sea of glittering lights. In fact, Ware dropped “The Platinum Pleasure Edition” of her album in June this year, which includes more disco hits such as “Please” and “Hot N Heavy.” Other white musicians, like Kylie Minogue and Lady Gaga, produced similar albums in 2020 that recall the height of the disco era. Perhaps the musician that garnered the most fame was Dua Lipa, whose album “Future Nostalgia” was praised for being the best disco-inspired album during a year where we were unable to physically be on a dance floor but could vividly imagine it through her lush tunes.

What was once a hated genre of music is now being celebrated because mainstream white musicians are at the center of its revival. In the process, white celebrities perpetuate the erasure of LGBTQ cultures in popular media.

I’m instantly reminded of Madonna’s “Vogue” single and music video that globally broadcasted voguing in the year 1990. She was hailed — and still is to this day — as an innovator for bringing this dance move by the same name into mainstream media and mastering its precise movements. However, voguing was a staple of the Harlem ball scene comprised largely of Black (including Afro-Latinx), gay, and trans folks three decades before “Vogue” hit the top of the charts. Vogue is a styled form of dance that takes poses from “high fashion and ancient Egyptian art [and] adds exaggerated hand gestures to tell a story and imitate various gender performances in categorized drag genres,” wrote Tsione Wolde-Michael in a piece for the National Museum of African American History & Culture.

These marginalized communities carved a world of their own where they could express themselves as loudly and extravagantly as they wanted. The rightful innovators are the LGBTQ folks of color that so beautifully took up space in this world by existing and living, even when straight white people spewed unrelenting vitriol towards them. Not to mention the terror they faced in the form of hate crimes and police violence.

To Madonna’s credit, the “Vogue” music video was choreographed by and featured Jose Gutierez Xtravaganza and Luis Xtravaganza, from the ballroom House of Xtravaganza. Both eventually went on to choreograph Madonna’s Blond Ambition tour. It’s great that people from the ball scene were involved in popularizing voguing. But Madonna profited the most, not the communities she used for inspiration.

The LGBTQ folks of color responsible for voguing gained little recognition in comparison. When someone mentions “Vogue,” most people don’t automatically think of Jose and Luis’ contributions and the Harlem ball scene. To the public, they are merely secondary characters to Madonna’s main role.

“What was once a hated genre of music is now being celebrated because mainstream white musicians are at the center of its revival.”

FX’s show “Pose” documented this well throughout season two, showing the impact “Vogue’s” popularity had not just on music charts, but in the ballroom community itself. In the show, dancer and member of the Evangelista house Damon Richards, played by actor Ryan Jamaal Swain, teaches voguing classes at the YMCA and is even scouted to be a dancer on Madonna’s Blonde Ambition Tour as the single surged in popularity across the country. But after no call-backs, a decrease in enrollment for his classes and the song no longer topping music charts, Richards becomes aware of the stark reality that is as his co-worker put it, “White folks [visiting] but never [moving] in.” He, like so many other Black (including Afro-Latinx) LGBTQ dancers, was left in the dust.

The mainstreaming of disco and ball culture are part of a larger trend of LGBTQ culture being appropriated. When this happens, the original history of these cultures is overshadowed by the celebration of white artists. Furthermore, the LGBTQ communities of color who create major cultural trends, fashion, and language rarely receive proper recognition.

Even popular phrases like “yass bitch,” “throwing shade,” “slay” etc. have been appropriated into the mainstream from Black LGBTQ culture. Many of these are rooted in the language of ball scenes. To see the obvious influence of these Black queer communities on culture today, one need only watch the 1990 documentary Paris is Burning. Elsewhere, you can find these phrases — along others like “fierce,” “werk,” and “spilling tea” — in RuPaul’s drag race, which has brought this language further into the mainstream since it debuted in 2009.

Today, white people who (attempt to) use this language are often seen as charming, whereas Black (including Afro-Latinx) folks can face discrimination for reclaiming terms coined by community members who came before them. When white people co-opt Black queer language, they effectively render it a cultural asset to be plucked and used when needed. LGBTQ folks of color are not valued for who they are as humans, but for what they can contribute to mainstream culture.

This erasure is so persistent that in an interview with Gay Times, Jessie Ware admitted she “didn’t fully understand the significance of [disco] as a genre for the [these communities]” when she started working on her album. Knowing this frustrates me. It makes listening to her music more complex because although she acknowledges the history, it feels secondary to her use of disco as an aesthetic.

I still listen to her album periodically; it’s hard not to when it holds sentimental value for me. However, I’m critical of her success and intentions regarding disco. The same goes for Madonna, Dua Lipa, and Lady Gaga. However, I believe that by learning history about the origins of disco and ballroom culture, we can begin to properly acknowledge and give LGBTQ communities of color the credit they deserve. Though it’s not enough, it is a start. Additionally, we need to give Black and Latinx LGBTQ artists honoring disco and ball culture a platform so they get recognition.

Last year in June, Victoria Monét released “Experience,” a disco-inspired breakup tune that was co-written with Khalid and produced by SG Lewis. Monét and Khalid penned in a thoughtful Instagram post that they were hesitant to release the song during a time when protests and action taken in support of racial justice were occurring around the world. But as they noted, June happens to be Black Music Month as well as Pride Month and Monét felt it was necessary to celebrate her queer identity.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBgOoCUjeqP/

Similarly, LGBTQ communities of color created disco and ball culture as a way to honor their multifaceted identities and feel liberated from traditions and norms that dictate they live and be a certain way. The emergence of these two cultures didn’t arise to make a statement to mainstream media or become popular on music charts but rather to build community with other LGBTQ folks of color and create a space where they could simply be. I hope we can honor the legacy of these cultures by remembering and acknowledging that Black (including Afro-Latinx) LGBTQ people deserve recognition for creating them. Disco and ball culture are more than an aesthetic or music meant to be danced to in clubs; it’s a celebration of LGBTQ identity, freedom and life.