Lin-Manuel Miranda Should’ve Listened to the Block

In the Heights’ sidelining of Afro-Latinx people still stings.

“This is my street. I smile at the faces I’ve known all my life. They regard me with pride. And everyone’s sweet, they say, ‘You’re going places.’” But how can I sing that when watching In the Heights left me confused and conflicted?

Based on the 2008 award-winning musical of the same name, In The Heights is the latest film produced by Lin-Manuel Miranda in his quest for media domination. Directed by Jon M. Chu, the movie musical follows locals of the uptown Manhattan neighborhood, Washington Heights, during a heatwave. Plans for the film version have been in the works since the stage version won five Tonys in 2008. Like many theatre fans, I’ve been waiting for its release for nearly 13 years. Unfortunately, the film misappropriates the stage musical’s core values and continues Hollywood’s erasure of Afro-Latinx people in depictions of Latinx communities.

As a young theatre nerd, I saw myself through this musical that talked about first-generation immigrant kids’ anxiety. Better yet, its backdrop was the neighborhood I spent my earliest years in. Block parties, bodega trips, and colorful characters on Riverside Drive in Manhattan illuminated my adolescence. An old man who lived at the corner of our street would give me bananas all the time (I aptly called him “Guineo”). Dominicans ran my preschool and my time at a Catholic elementary school reflected the Black and brown demographic of my block. I naively thought white people only existed on television, until a blonde German boy joined my mom’s daycare.

My plight with identity arose when I moved to Newburgh, New York and didn’t look like any of my peers. I didn’t exactly resemble the Black girls or the other Latina girls. Back then, there weren’t many Dominican families in Newburgh. I tried to fit in with the Mexican students, but our cultures were pretty different. They heard banda music and ate tamales at home while I heard bachata and ate mangu at home. They had naturally silky straight hair while my curly hair was straightened and frizzy. Despite these differences, mainstream American film and TV decided we were a monolith. And due to the dismal amount of Latinx film and TV projects produced each year, media depicting predominantly light-skinned or white Mexican Americans were all I had.

In The Heights spoke to me like no other form of media had because it told the story of my birthplace. Hearing claves and Latin melodies in a successful Broadway show felt so gratifying. The characters, who embodied multiple cultures within the Latinx Caribbean diaspora, faced their struggles by banding together as a community. At age 12, I finally saw people who looked like myself and my family on stage.

The film version — scheduled for 2020, but postponed by the pandemic — had built up a large amount of anticipation. Warner Bros. won the bid after The Weinstein Company became embroiled in its namesake’s scandal. Before that, Universal Pictures canceled the project because Miranda was unwilling to cast big celebrities like Jennifer Lopez.

“I still don’t understand how we went from being the Tony-winning show that everyone couldn’t wait to adapt to international telling everyone, ‘We can’t make the movie at this number, you don’t have a star, and unless you get this international recording artist to basically lose money by doing this movie because they’re all on world tours, you can’t make this movie!’” Miranda told Indiewire.

The production moved forward with Warner Bros., filming in Washington Heights in 2019. When the first teaser trailer dropped, concern dampened the excitement around the project. Washington Heights, a neighborhood known as a majority Black and brown Caribbean community, was lighter in complexion on screen. The film’s release in theaters and on HBO Max sparked further discussions about colorism and representation. The box office numbers were disappointing for the studio. The film trailed behind familiar franchises like The Conjuring and A Quiet Place.

These discussions came to a peak following an interview of cast members and the film’s director, Jon M. Chu, by The Root’s Felice León in early June. León asked Chu and the cast about the lack of Afro-Latinx people in the film’s main roles and Chu responded by mentioning In The Heights’ Afro-Latinx background dancers. Melissa Barrera, the Mexican actress playing Vanessa, said a lot of Afro-Latinx talent were present during the audition process. “And I think they were looking for just the right people for the roles,” Barrera said. “For the person that embodied each character in the fullest extent.”

What these comments failed to acknowledge is how frequently Afro-Latinx characters are excluded in Hollywood. Afro-Latinx performers made up less than 19 percent of Latinx film actors and 17 percent of Latinx TV actors from 2010 to 2013, according to a report commissioned by the National Hispanic Foundation for the Arts. León pointed out that the film relegates Afro-Latinx performers to background actors in the hood and beauty salons.

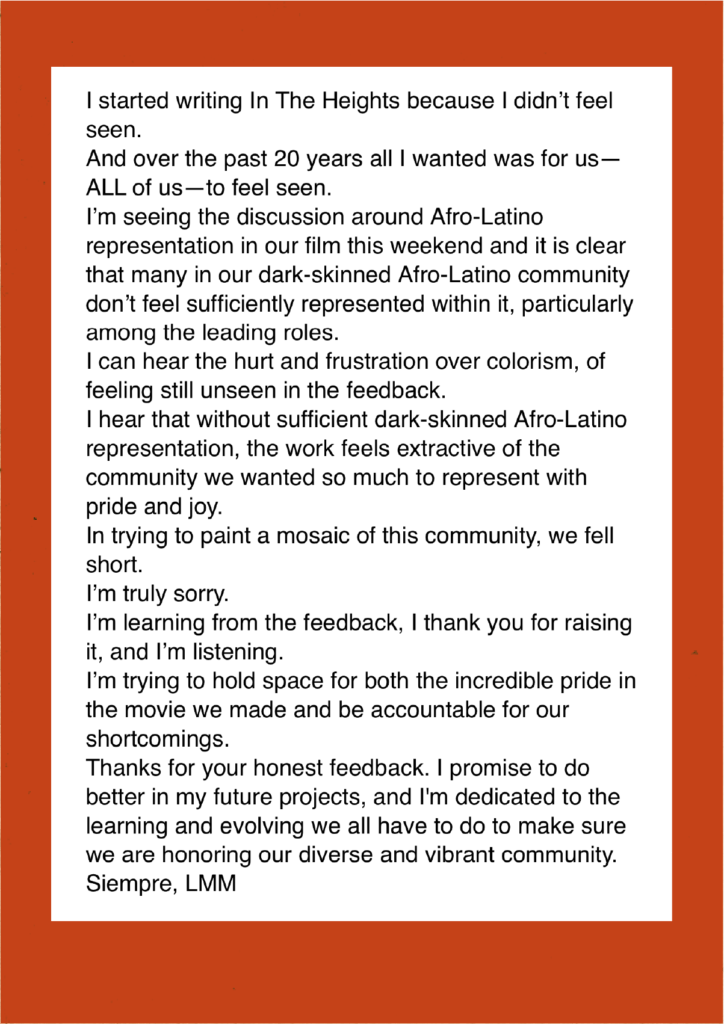

Four days after the film’s premiere, Miranda issued a statement about its casting and apologized for falling short “in trying to paint a mosaic of this community.” In the post, he promises to do better in future projects.

Lin-Manuel Miranda posted this statement on Twitter.

I spent a lot of time contemplating my stance on all this. As a Dominican woman born in the Heights, I’m heartbroken by the erasure of Afro-Latinx people. I’m also cognizant of my privilege as a light-skinned Dominican woman with a 3b curl pattern. But it’s hard to enjoy something while mourning the erasure of a certain group. How can I like this when it ignores people I care about? A group encompassing my tíos y tías, my cousins on the island, and those in the States? Hollywood’s view of Latinx culture as one thing robs viewers of the joy of seeing themselves accurately portrayed on screen.

By nature, musicals on stage and in film have different rules and limitations. A film audience might prefer more dialogue between musical numbers. Quiara Algería Hudes, the musical’s playwright, returned to adapt the show for film. One major change for In The Heights establishes one character, Usnavi, as a narrator telling a few kids (and the audience) his memories of Washington Heights. The flashback format implies Usnavi’s storyline is more central to the film than those of other characters. Usnavi introduces his block and the people who live on it. He aims to return to the Dominican Republic and pines after Vanessa, a young woman who works at a salon and dreams of escaping her alcoholic mother — which is not mentioned in the film — and moving downtown.

While this pairing plays a role in the musical, their story in the film eclipses that of the other main couple: Nina and Benny. Nina is a 19-year-old Stanford dropout dealing with the guilt of leaving college while her parents struggle to succeed. She courts Benny, a Black man who works with her father at a taxi dispatch. Their love story unfolds on stage slowly, but the film immediately positions Benny and Nina as exes who broke up before she left for Stanford. A part of “The Club” originally sung by them is given to Usnavi and Vanessa instead. Their relationship in the musical also addressed anti-Blackness within the Latinx community. Kevin, Nina’s father, explicitly disapproves of their relationship because of Benny’s race. The film omits this. I can’t help but wonder if these changes were made to avoid difficult conversations about racism.

The film’s Nina and Benny. Graphic by Sara Schleede.

Anti-Blackness is passed down in Latinx communities through phrases like “pelo malo” or “pelo bueno” (bad/kinky hair or good/straight hair) and jokes about marrying light. It’s a vestige of colonialism that followed the Latinx diaspora. Afro-Latinos in the U.S. face racism within both American culture and Latinx culture. If the film truly wanted to show the world what Washington Heights is like, it needed to validate the experiences of the Black people who live there.

Miranda, in his quest to get In The Heights both on Broadway and on screen, had to gain the approval of many white people. As he sought financing for the stage musical, producers wanted the plot to have higher stakes. Specifically, they wanted a more dramatic explanation for Nina dropping out after her first year at Stanford. “Like, ‘Why isn’t she pregnant? Why isn’t she in a gang? Why isn’t she coming out of an abusive relationship at Stanford?’ Those are all actual things I was pitched,” Miranda told Rebecca Rubin of Variety in April. “Because the pressure of leaving your neighborhood to go to school is fucking enough. I promise.”

While Miranda stood his ground for the stage musical’s plot and the film’s cast of mostly unknown actors, he compromised the show’s original grit and conflict. The play presented a Latino community free of the usual stereotypes of gang and drug violence. Its grit comes from the interpersonal disputes between an immigrant and their first generation child, a black man and the Latinx neighborhood he lives in, and an abuela and her community of non-related grandchildren. He missed the actual stories and faces which made his first musical so great.

Miranda’s work has evolved since he first did a one-act version of In the Heights at Wesleyan University in 2000. The insane success of his second project, Hamilton, made him a household name. Hamilton exuded an optimism for the establishment and racial harmony that could have only succeeded during the final years of the Obama administration. While Hamilton is a liberal viewing of U.S. history, In the Heights is a thoughtful snapshot of a single neighborhood. The film adaptation departs from the musical’s overarching message because it more closely mirrors the liberal colorblind optimism of Hamilton. The musical explores struggle, gentrification, and turning to your community in times of need, whereas the film prioritizes talk of individualistic dreams.

When the musical closed on Broadway in 2011, Miranda came back as Usnavi after the bows and recited a rap. I remember Miranda sincerely rapping that a white high schooler in the Midwest playing Usnavi is “gonna know what a Puerto Rican flag is.” I used to find that part so funny and inspiring, but now I’m just heartbroken. Representation is not just about sharing our culture to be used by white kids who can’t roll their r’s. It’s about having our whole culture respected.

Latinx people know what it’s like to feel othered, and to other people within our own community feels like a betrayal. It hurts because it comes from an artist who played a major part in my story. I wrote about In The Heights in my admissions essay for college. I graduated this year and was the first in my family to get a Bachelor’s degree. I held onto this musical so tightly I didn’t believe I should expect more from mainstream media. I see the sincerity in Miranda’s statement, but it’s not my place to forgive. That neighborhood in Manhattan holds so many stories and they deserve to be told.