More than six months after the killing of Breonna Taylor, a grand jury in Kentucky voted to charge former officer Brett Hankison with three counts of wanton endangerment in the first degree. The other two officers involved in the shooting, Jonathan Mattingly and Myles Cosgrove, were not charged.

The news comes after the city’s mayor, Greg Fischer, declared a state of emergency this week due to the potential “civil unrest” in response to the grand jury’s decision. Fischer also ordered a curfew from 9 p.m. to 6:30 a.m. from Wednesday to Friday. In addition, Louisville Chief of Police Robert J. Schroeder placed barricades and city vehicles downtown, barring officers from requesting time off in anticipation of protests.

On March 13, three plainclothes LMPD officers — later identified as Mattingly, Hankison, and Cosgrove — were ordered to execute a no-knock warrant at Breonna Taylor’s apartment. According to the New York Times, the orders were changed prior to a “knock and announce,” meaning the officers had to announce themselves prior to entering. According to Kenneth Walker, Taylor’s boyfriend, he and Taylor heard banging but did not hear the officers announce themselves. Eleven other witnesses corroborated Walker’s claims that they did not hear the officers announce themselves. The three officers involved were adamant that they did in fact shout “Police!” Only one witness confirmed the officers’ claim, but said they only heard the officers shout “Police!” once.

After hearing the aggressive knocking, the officers entered Taylor’s apartment. Walker, who was licensed to carry a firearm, believed they were experiencing a home invasion and shot at the police once — injuring Jonathon Mattingly. The three officers responded by firing twenty rounds. Brett Hankison fired ten of the twenty rounds sent in the couple’s direction. An ambulance arrived soon after the shooting, with two other officers attending to Mattingly, but not Taylor. Taylor received no medical attention for over 20 minutes after she was shot. According to Taylor’s autopsy, she received five gunshot wounds to the body.

On June 23, Hankison was fired for his actions during the raid, during which Chief Schroeder stated Hankison, “displayed an extreme indifference to the value of human life” as he “wantonly and blindly fired ten rounds.”

According to Kentucky’s legislature, a person is guilty of wanton endangerment in the first degree when, “under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to the value of human life, he wantonly engages in conduct which creates a substantial danger of death or serious physical injury to another person.” The charge against Hankison is a Class D felony and carries a prison sentence up to five years. If the charges are run concurrently, Hankison will face up to five years of prison time, but if they are not he could face up to 15 years.

The Taylor family’s attorney, Benjamin Crump, tweeted in response to the news, calling the charges of wanton endangerment “outrageous and offensive.” Crump shed light on the three charges against Hankison, noting that Hankison was not charged for the killing of Taylor, but for potentially endangering the lives of her neighbors.

Earlier this month, the City of Louisville agreed to a $12 million dollar settlement with the Taylor family after they filed a wrongful death suit against the city on May 15. Mayor Fischer indefinitely suspended no-knock warrants on May 29.

When police killed Breonna Taylor in March and George Floyd in May, protests against police brutality and anti-Black racism erupted across the country. Activists once again took to social media platforms like Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok to distribute calls to action.

With the spread of resources and information also came a slew of public statements and apologies from name-brand corporations. Wendy’s, a fast food chain with a brand built on organic ingredients and ethical animal practices, quickly took to Twitter and the company blog to voice support for racial justice.

“For all who respect life and value equality, we hope that there will soon come a calming to the unrest that so many communities are experiencing today,” wrote Wendy’s CEO Todd Penegor in the June 1 blog post. “At the same time, we understand the outrage and raise our voices to say enough is enough. We can’t achieve change on our own, but we do need to be part of the solution.”

But behind the company’s public attempts at “woke” branding are blatant actions that directly harm Black and Latinx people. Two of the most glaring examples are Wendy’s refusal to join the Fair Food Program, which protects the rights of farmworkers in corporate supply chains, and board chair Nelson Peltz’s financial support of Donald Trump.

From 2016 to 2017, Peltz individually contributed more than $85,000 to the Trump campaign and hosted a 2020 reelection fundraiser for the president with a $580,600 entry fee per couple. Wendy’s has not commented on Peltz’s campaign contributions, and did not respond to The Interlude’s multiple requests for comment. The company has said it, as a corporate entity, has never contributed to any presidential campaigns, tweeting: “We never have and will never contribute to a presidential campaign. For the record our CEO has always kept that same energy too. Facts.”

However, Wendy’s willful separation of itself from Peltz’s financial support of Trump — who has normalized racism against Black and Latinx communities — speaks loudly of Wendy’s complicity in racist behavior.

During protests and boycotts against Wendy’s, activists and farmworkers with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (the group that developed Fair Food) have specifically targeted Peltz, who, as of 2019, is estimated to own 44.4 million shares in Wendy’s. Peltz also serves as the CEO of Trian Partners, Wendy’s largest shareholder. As a high-power executive and a significant Wendy’s shareholder, Peltz has the authority to sway the company towards Fair Food membership.

Although Fair Food’s membership includes McDonald’s, Burger King, Subway, Aramark, Walmart, Taco Bell, KFC, Whole Foods, Stop & Shop, Trader Joe’s, Chipotle, and Pizza Hut, Wendy’s has yet to join. The company publicly refused to join Fair Food in 2016, citing the program’s practice of charging buyers one cent more per pound of tomatoes in order to provide pickers with a bonus.

Even after CIW protests were held outside of his Trian office in New York in 2018, Wendy’s has not made any changes. The company has also been pressured by concerned shareholders to share more specific information about its methods to assess human rights risks in the supply chain, arguing that the company’s quality assurance checks don’t address workers’ rights, even claiming that the checks are pre-announced and supervisors may even be coached through questioning of worker treatment. Wendy’s declined to provide any further information other than the company Code of Conduct.

In 2019, the issue of Wendy’s unwillingness to join Fair Food came up again when the company claimed that a recent switch to hydroponic, greenhouse-grown tomatoes would provide adequate social benefits to farmworkers. CIW activists argue that greenhouses are plagued with the same workers’ rights issues as farms, claiming that Wendy’s only made the change to enhance their public image as a brand that uses organic, sustainable produce.

“What good is eating an organic tomato when it’s tainted with human rights abuse?” said CIW activist Lupe Gonzalo in an interview with The Interlude. “For years, Wendy’s has tried to hide the truth behind their trendy brand. For a company like Wendy’s to put the safety of their women workers on the sideline is really unacceptable.”

After more than 12 years as a farmworker, Gonzalo knows all too well the grim reality of rampant abuse in the produce fields. Immigration status, language barriers, and fear of retaliation keep many women from reporting sexual harassment or assault, especially women of color. A 2010 study by in the Violence Against Women journal found that 80 percent of the 150 migrant workers interviewed in California had experienced sexual harassment on the job.

Wendy’s Code of Conduct doesn’t have any specific language pertaining to the prevention or reporting of workplace sexual abuse, only stating that suppliers are “expected” to comply with the Fair Labor Standards Act. Other than that, the code mostly asks suppliers to “do the right thing” and “treat people with respect.” In an outline of the company’s supply chain practices, Wendy’s even labels itself as a leading example of ethical practices in the industry.

“Wendy’s lovely, glossy consumer responsibility report not withstanding, they’re still not ready to truly guarantee the human rights of farm workers in their supply chain in a way that is transparent [and] verifiable,” said Noelle Damico, a former press coordinator with CIW who also served on the board of directors for the Fair Food Standards Council. “What we’re looking for Wendy’s to do is to match those nice words about social responsibility with the gold standard of actually realizing social responsibility, which is the Fair Food Program.”

The Fair Food Program is a specific set of workers’ rights standards that member corporations and their suppliers must uphold, with immediate consequences for buyers or growers who don’t comply. When corporations join the Fair Food Program, a contractual agreement is made to suspend all purchases from growers who fail to comply with the program’s detailed Code of Conduct. Offending growers who fail to provide documented evidence of reform will be removed from Fair Food entirely. The Fair Food Standards Council conducts regular audits of member growers and offers worker-to-worker Know Your Rights workshops.

Although Fair Food is willing to certify Wendy’s current suppliers, the fast food company still declines membership. Instead of allowing farm inspections from the Fair Food Standards Council, Wendy’s relies on third-party auditors. Among these auditors is SA8000, the controversial firm that certified Bioparques de Occidente, an infamous tomato farm in Mexico with known forced labor practices, involvement in human trafficking, and severely unsafe working conditions. The firm also inspected and certified Ali Enterprises in Pakistan, a factory where almost 300 workers were killed in a 2012 fire, trapped because of the building’s barred windows and lack of functioning fire doors. The auditing practices that Wendy’s relies on again came into question in May when a coronavirus outbreak at Green Empire Farms infected 171 migrant workers and caused the biggest spike in upstate New York cases at the time. Mastronardi Produce, the owner of Green Empire, is one of Wendy’s suppliers, according to The Nation. In a September interview with Bowe, Wendy’s spokesperson Heidi Schauer would not answer questions about when Mastronardi was last inspected for safety or audited for workers’ rights abuses.

When Wendy’s clings to private inaction against the unethical treatment of migrant workers within the company’s supply chain, but utilizes social media to publicly brand itself as an ethical corporation, Wendy’s adds itself to the list of the countless brands participating in performative allyship. But as Wendy’s fails to protect the Black and Latinx farmworkers in its supply chain, Wendy’s further attempts at progressive branding have only exposed the company as the most performative ally of them all.

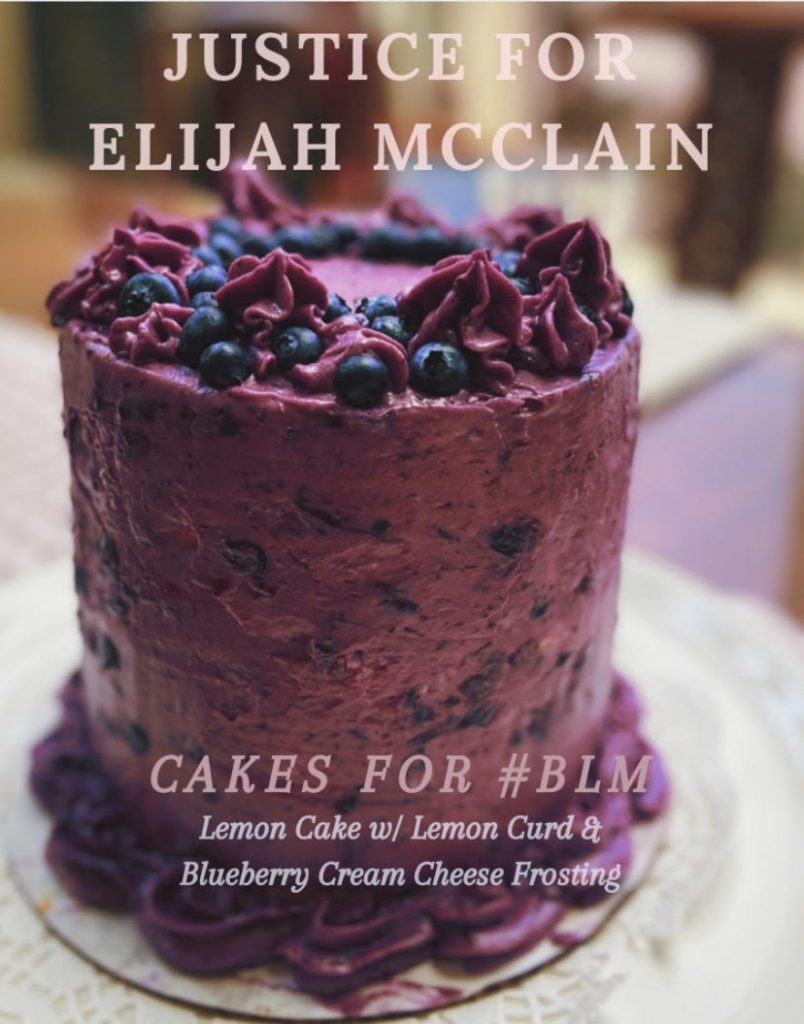

Rukmini Das usually only bakes once a year, on Thanksgiving. But, like many other Americans, she started baking more often when stay-at-home orders were implemented in late March during the COVID-19 pandemic’s spread in the United States

Das, 24, left Princeton, N.J. in March to quarantine with her family in Houston, Texas. She was working from home as a strategy and advisory consultant, but in her spare time, she baked: cakes, pies, banana bread, and more. Her cakes caught the attention of one of her friends, who told Das she should sell them — but Das had no interest in becoming a professional baker.

But when protests for racial justice erupted across the country after the police killing of George Floyd, and hundreds of social media calls to donate to anti-racism organizations popped up, Das immediately thought of doing a bake sale. Since she had returned home, she felt sad that she couldn’t go to protests in New York.

“That’s the most classic, old fashioned way to raise money,” Das told The Interlude. “In Houston, there were so many things going on, but I didn’t personally feel super comfortable just because I didn’t want to put my family at risk by going in person.”

Photo courtesy of Rukmini Das

Das quickly set up an Instagram account, Cakes for BLM, and a straightforward process: people put in an order, they (or Das, if the customer doesn’t have a preference) choose an anti-racism organization, Das vets the organization, and a donation is made to the organization in exchange for a cake. She tends to make two to three cakes a week, and people in the Houston area can pick up orders from her once they’re complete. Since starting the initiative in June, Cakes for BLM has expanded to include a marketing team and three more volunteer bakers who found her through Instagram — one in New Jersey, one in California, and another in Houston. They have also been able to donate over one thousand dollars to anti-racism organizations like the Innocence Project, Black Women’s Blueprint, and the National Black Justice Coalition.

For Das, the bulk of Cakes for BLM work takes place toward the end of the week, as she works long hours in consulting. She starts baking on Thursday and has the orders ready for pickup by Saturday or Sunday. When she first started out, most orders would be placed via Instagram direct messages. Now, though, Cakes for BLM has a website where customers can place orders.

Photo courtesy of Rukmini Das.

Cakes for BLM usually takes a minimum donation of $50. Das sets aside about $5 to $10 to cover the cost of ingredients, regardless of whether people choose to donate more. After an order is fulfilled, it gets highlighted on the Instagram page, where Das provides details about the organization proceeds were donated to, in order to spread awareness.

“There have been people who reach out to me being like, ‘Oh, that’s really cool. I’m gonna donate there,’” Das said. “Because we don’t live in the same city, they can’t get a cake for me, but they can see that post and be like, ‘That’s a really cool organization, I want to donate there.’”

Initially, she would choose an organization based on lists of anti-racism organizations in need of funds that were being passed around on social media, but she’s also open to customers suggesting others that they are interested in. Das vets each organization to make sure they are specifically U.S.-based anti-racism initiatives.

“There’s a lot of grassroots ones or local ones that I wouldn’t have known of,” Das said. “I’d never heard of them, and then other people suggested and they’re like, ‘Oh, actually, I want to donate here.’ And by opening it up for people to donate to whatever organization or fund that they would like, it actually opens up a lot more knowledge even for myself.”

View this post on Instagram

Nearly three months after making the first donation, she’s still seeing traction. Now, she’s looking into her long-term goals. She acknowledged that it’s unsustainable for her to bake two to three cakes each week for the rest of her life, but she’s hoping that after the time comes where she can’t continue to bake every week, Cakes for BLM will have expanded to include many volunteer bakers who can continue raising money for anti-racism organizations.

“It’s a fun pastime that a lot of people have,” Das said. “And one of the things I think a lot of bakers have in common is that we love to share our food. You know, part of it is the artistry of making something that looks beautiful.”

Photo courtesy of Rukmini Das.

Das also thinks that Cakes for BLM can serve as a long-term investment in anti-racism efforts. She noted that people are looking to make their contributions to the Black Lives Matter movement last — people don’t just want to donate to an organization once and then forget about them.

“One way is obviously to do repeating donations — you know, put your card down and forget about it,” Das said. “There’s a bunch of ways to do it. And this could just be another option, right? How cool is it that like, ‘Oh, next time I order a birthday cake, why not order through Cakes for BLM If there’s one nearby, because then that money is going to a good cause as well.’”

Tiz Giordano, a North Carolina community organizer and essential worker, was horrified when they came across a Reddit thread of a University of North Carolina COVID dorm occupant. Even before, they were well aware of the UNC’s brewing COVID crisis, partly because they live by student housing and saw a large number of maskless students partying and partly because they’re in a UNC student meme group, where tragicomic images of frightened students filled the feed. But it wasn’t until that moment that Giordano decided to do something about it.

The thread Giordano came across recounts a student’s time living in Craige Residence Hall, a dorm converted by the university for students to quarantine who might have been exposed. The student returned to on-campus housing to avoid an unstable home situation, but shortly became ill with COVID-like symptoms and was forced to relocate to the quarantine dorm. There, they received little to no care — no checkups, screenings, or monitoring while waiting to be tested — from the university. The student wasn’t alone in their experience: less than a week after classes began, the university identified several COVID clusters and shortly moved classes online.

Giordano knew that marginalized students would be those most affected by lackluster governance and irresponsibility of what they described as “mostly frat and sorority” members. As a “Chaepel Hill / Carrboro Mothers Club” Facebook group member, they were aware that many local parents wanted to do something to help them. So Giordano decided to start pairing up those in need with parents willing to provide a helping hand. They created two spreadsheets, one for the students and one for the parents, and then dispersed them on social media. The process is pretty straight-forward: students fill out the form with some basic information about themselves, and ask for what they need help with. The parents — or anyone wanting to help — can provide details of what they are able to offer. Based on the specific needs, such as “queer,” “in recovery,” “none religious,” “Immigrant,” “black only,” “sexual assault survivor,” Giordano makes a match.

In three first three days, 19 students and some 125 families filled out the request forms. Now, just three weeks after the program started, Giordano counted 35 students in need, and 240 families willing to help.

While many parents were willing to provide resources, such as care packages, legal help for immigrants, and even housing, Giordano said it was the emotional support that the students — majority of whom were freshman, queer, and foreign-born — craved the most. “They say: ‘I’m scared. I don’t have an affirming family. My family is in Beijing. My family is in a different time zone,’” Giordano recalled, “‘I just want someone to talk to.’”

Giordano gave an example of one student who specifically asked for a Black parent because the student was living in a predominantly white area. The two were able to make a connection, fostering emotional support the student needed to adjust to their situation.

One of the participating moms, Heath Sledge, who found the forms on a UNC subreddit agreed, saying the California native that she was paired with was “very freaked out,”

stuck in a hotel room awaiting test results that had no known ETA. Sledge believes he primarily “needed emotional support.” Even though he was missing a number of essential items, including a phone charger, it was panic caused by all of the unknowns that weighed on him the most. After talking with him however and reassuring him that he wasn’t alone in this, Sledge said that he was able to resolve the missing item issues himself.

“I’m really struggling right now because I have no parental figure in my life so navigating adulthood/college is hard enough without all this COVID shit,” said one of the students in the comment section of Giordano’s Reddit thread about the initiative, “Thank you so much for doing this.”

UNC shifted to 100% online learning on Aug. 17. But the matching service has no intention of shutting down, as not every student is able to go back home. Some students live with their grandparents and fear bringing the virus back to them. Others, similarly to the AMA author, have unstable home situations and rely on the university for food and shelter.

But Giordano’s willingness to help UNC students wasn’t risk free. Their spouse is immunocompromised and recently lost his federal unemployment, forcing the couple to apply for food stamps. The activist believes that they will be able to rely on a local mutual aid fund if the government assistance isn’t enough.

“It’s time to stop believing in authority and start believing in each other,” Giordano said. “These are youths who have been failed by the institutions and adults in their lives. No brainwashed 18-year-old whose decision skills have not fully developed should die because some shitty, decrepit GOP politician wants to line his pockets with cash from donor bags.” Sledge echoed this sentiment saying she was “really mad” at the UNC administration for their handling of the situation. “Everything is falling on the students’ shoulders,” she said, “A lot of them are young and have never lived at home before. They don’t know how to navigate a lot of this stuff.”

“Mutual aid funds are stepping up in ways governments are not,” Giordano said. They hope other cities will take note and create similar initiatives to help students. But the one thing Giordano wanted people to remember is that regardless of personal experience in community organizing, “anyone in the community that sees a hole can fill it.”

As young adults flock to colleges and universities around the country, it has become increasingly clear that for some universities, the safety of students and employees is a secondary concern to financial comfort. Given the emergence of campus COVID-19 outbreaks across the country, coupled with lethargic or nonexistent responses to complications from bringing students back to campus, it’s clear that U.S. institutions see their students as expendable cash cows.

The coronavirus pandemic upended the look and feel of classroom learning all the way back in March, forcing schools around the country to rapidly adapt curriculum and guidance for in-person, hybrid, and online learning. But now, as schools reopen and campus COVID cases top 26,000, an increasing number of reopening plans are falling apart. Just a week after moving students back on to campus, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill announced an outbreak of four COVID-19 clusters and moved undergraduate learning online. Shortly after, the University of Notre Dame and Michigan State University followed suit. (Notre Dame said classes would be online for the two weeks; Michigan State did so for the remainder of the year.) New York University made headlines for providing quarantine students with insufficient meals, or in some cases, no meals at all. The blunder ended up costing the university a pretty penny; NYU had to provide students $30 per day for dinner delivery, all because the university hired a company with a history of giving vulnerable children spoiled food instead of taking the time to make sure proper nutrition would be delivered to students stuck inside their city dwellings.

While the pandemic chipped away at budgets at institutions across the U.S., a larger issue of university cash flow has been mounting for years. American higher education programs have increasingly relied on tuition money to operate. In 2017, more than half of U.S. states relied more on tuition revenue than public funds, according to the Association of American Colleges & Universities. For the 2018–2019 school year, nearly 50% of the University of California’s projected revenue increase came from student tuition and fees. Private institutions haven’t fared much better. Twenty percent of Harvard University’s 2019 revenues came from tuition; 43% came from philanthropic gifts. Fifty-seven percent of New York University’s 2019 operating budget relied on student tuition and fees; another 10% came from housing and dining. When colleges shut down in the spring, many colleges pro-rated or returned some housing and meal plan fees, but clung to tuition dollars while they invested millions in online learning. In April, Moody’s Investors Service predicted that returning to in-person classes would make impacts on budgets “more manageable,” especially if international students continued to pay tuition. It appears institutions took note. Institutions seem more willing to risk the health of students and staff to make ends meet. But with fewer resources, a fledgling public health infrastructure, and a rush to secure tuition, preventing the spread of a deadly virus has proven to be near impossible. Chapman University’s president told the New York Times that the school spent $20 million prepping the campus technology and public health. He estimated that moving school fully online would cost the university another $110 million. The move, coupled with a lack of state and federal aid, put even the most well-off institutions, like UNC, in an uncomfortable financial position. For public universities and small private colleges, the pandemic has proven to be financially disastrous.

But for families, many of whom struggled financially during the economic crash fueled by the pandemic, sending students back to a lackluster educational experience at full price may be more disastrous. Parents and students across the country have voiced concerns about the cost of a college education in the middle of a pandemic, arguing that paying full price or increased tuition for online learning isn’t worth the cost. More than 1,100 petitions calling for tuition refunds have been posted on Change.org. Some students who can afford to take a gap year have elected to do so instead of paying for online schooling. Twenty percent of Harvard’s incoming class deferred enrollment. And already, parents have sued schools including George Washington University, the University of Connecticut, and Miami University over discrepancies in online learning quality. Perhaps more pressing than the fate of universities moving to online schooling, is the safety of students at schools where reopening for in-person learning was the top priority.

As campuses continue to reopen, concern has grown over universities’ ability to control potential sources of outbreaks both on and off campus. Texas A&M University had more than 690 positive cases in the first three weeks of school. The University of Alabama has more than 1,000 cases only two weeks into classes. And the University of Southern California has 104 cases in what is being qualified as an “‘alarming’ surge” by on-campus media. Even when universities have quarantine protocols that limit time outdoors and interacting with others, and promote hand hygiene and mask wearing, students have found ways to defy them. Videos of Syracuse University students ignoring social distancing and quarantine protocols went viral. Photos circulated of Greek fraternity and sorority parties at University of Georgia, despite reports that a university employee died from COVID-19 just a few weeks before. Georgia Tech also has COVID-19 clusters linked to Greek life. And the University of Miami has more than 180 confirmed COVID-19 cases, even though the university has suspended students for violating campus safety rules.

The number of reported cases (with more likely to come) and rolling closures, is cause for concern. The safety of students and staff appears to be declining in the few weeks campuses have been open. But the conflict between university messaging and the safety concerns paint a much darker picture: students and staff are sounding the alarm, but universities turning a blind eye.

On July 1, a Yale professor told students in an email that they “should all be emotionally prepared for widespread infections — and possibly deaths.” The email, obtained by the Yale Daily News, also told students they should “emotionally prepare for the fact that [their] residential college life will look more like a hospital unit than a residential college.”

It is unclear whether the professor’s intent was to encourage students to stay home, or to comply with campus safety protocols. Clearly, enough was amiss that a psychology processor felt the need to tell students to brace for death. Regardless of whether the university approved the communication, the fact that such an email was sent to students with no apparent reconsideration of student safety shows just how little Yale cares about the safety of its students when it could be making money from student housing.

But students at some of the already-affected schools said that they have been sounding the alarm for months about their universities’ ability to keep students and staff safe. A student at the University of Texas recently took to Twitter to complain about the university’s response after serving on a reopening committee alongside administration. “We asked UT admin to invest in preventative measures for COVID — free face masks, universal COVID testing, free PPE for staff,” Vinit Shah wrote on, “They refused.”

In a follow-up post, Shah encouraged students to re-think their plans to return to campus and alleged that UT’s administration’s first priority was profit — not student safety.

It took viral TikTok videos for NYU to feed quarantined students more than a bottle of water and watermelon chicken salads.

@onetoomanytwizzlersok but can somebody tell me what watermelon chicken salad tastes like? #nyu #nyufood #nyutiktok #watermelonchickensalad #fyp

Universities’ response to criticism has been lackluster at best. NYU released a Twitter statement that placed blame on its vendor, Chartwells. And in a decidedly immature move, Purdue University published a list of “compliance naysayers,” with quotes from news articles and experts questioning the university’s readiness and ability to prevent an outbreak. This public mocking over legitimate concerns for student safety demonstrates an unwillingness to prioritize students over profit. (Sorry, President Daniels, you’ll have to add The Interlude to that list.)

Ranging from negligence to apparent malice, it has become increasingly clear that students at universities across the nation cannot depend on their schools to keep students and staff safe. The decision to bring students back without proper planning or contingency measures shows just how much universities anticipated they would need students to return in order to sustain themselves.

But it didn’t have to be this way.

Harvard decided in July that it would move undergraduate courses online. The University of Pennsylvania also decided to hold classes online. And despite making a last-minute change that left some students who came to New York City early scrambling, Columbia called off its in-person undergraduate classes two weeks before the semester was scheduled to start (although after some out-of-state students moved to New York to quarantine.) The university reduced fees and returned room and board for students forced to take classes from home. But these educational institutions have a brand value that may sway students to stick around, even when the education is online.

Without a bailout package to help schools stay afloat or federal oversight of campus reopenings, students will continue to be bled dry for tuition money, whether online education is on par with in-person learning or not. What has become increasingly clear is that for many universities, the safety of students and employees is a secondary concern to financial comfort. And the ramifications of that choice are deadly.

With more than 26,000 COVID-19 cases, it’s only a matter of time before students and staff die from infections they contracted on campus. If the national death rate holds for college students and the older adults they interact with as the U.S. gears up for a second wave of virus outbreaks, we can expect to see at least 700 deaths resulting from reopening college campuses. (And that is not counting the tertiary community spread that could occur by sending students home after they test positive.)

Since universities don’t seem to care much for student health, perhaps they will take note of the liability posed by deaths on campus. While it’s unknown how the courts will determine what universities’ obligations are to protect the health of its employees and patrons, lawsuits are bound to result from deaths related to campus COVID-19 exposure. If current budget constraints were a concern, having to pay millions in settlements to families of dead students and staff could tank the healthiest of university budgets. Not to mention the emotional damages students and staff may be entitled to after enduring such a traumatizing school year. After all, it’s hard to squeeze money from your cash cows when they become skewered beef.

The last time Clarke Central High School senior Owen Donnelly, 17, saw his newspaper staff was in March. The Georgia school’s newsmagazine, The ODYSSEY, had won several awards at the Southern Interscholastic Press Association Convention, and the staff was fired up to finish off the semester strongly.

“I was like, ‘Okay, we’re going to go back to school, we’re going to finish off, and it’s going to be awesome,’” Donnelly, a current co-editor-in-chief of The ODYSSEY, told The Interlude. “And then it just didn’t happen. We didn’t go back to school.”

After the coronavirus pandemic crept into the United States in mid-March, Clarke County, along with other Georgia school districts, moved to online learning. While most students have faced numerous challenges adjusting to remote instruction, high school journalists across the state had to quickly figure out how to navigate reporting on their schools as a team while being apart indefinitely.

Georgia has faced a particularly tumultuous few months during the pandemic. Brian Kemp was the first governor to reopen a state in April, earning criticism from the president. Throughout the summer, Kemp publicly squabbled with Georgia mayors over mandating mask-wearing in their cities. The state doesn’t have a uniform plan for school reopenings, leaving decisions largely to individual counties and districts. And now that the 2020–21 academic year has started for many Georgia schools — with some fully returning to in-person learning and others conducting all classes remotely — student editors-in-chief have to take on an entirely new role and motivate their staffs without the sort of magic that comes with being in a newsroom run by dedicated teenagers.

“We just have to plan out things a lot more,” Donnelly said. “We’re planning out workflow and what everyone’s going to be doing a lot more than, I think, we would in previous years just because of this momentous challenge that we’re about to be facing.”

Members of the ODYSSEY staff. Photo courtesy Owen Donnelly.

For Donnelly, keeping younger staff reporters engaged has been difficult, especially since Clarke County will start the fall semester remotely. He said that since many students haven’t done much for the paper since March, they seem uninterested and laid-back, though there are, of course, those who are enthusiastic and always ready to hop on. Not being with his peers has also been challenging for him personally — Donnelly likes being around people, and only seeing people online has been affecting him. Still, though, he and his co-editor-in-chief, Naomi Hendershot, are still committed to staying optimistic and making things as fun as possible.

“We’re going to try to do staff bonding stuff outside, distanced,” Donnelly said. “I don’t know if it’s like kickball or group yoga or something — to just see each other, you know? And get people in that mindset of like, ‘We’re a team and we’re working together, even if it’s from home.’”

The idea of starting a leadership role from home is daunting for some high schoolers. Stephany Gaona-Perez, a senior at Cedar Shoals High School in Clarke County, said that when school initially went online, she was worried that she wouldn’t be ready to be co-editor in chief of Cedar Shoals’ Blueprints Magazine. She wanted to be fully trained and prepared to help guide newer students. She was also concerned about not being able to dedicate enough time to the publication.

“Me being a senior, I’m currently looking at scholarships, looking at colleges, trying to do more community service so I can have that on my applications,” Gaona-Perez, 17, said. “But honestly, with what we’re doing with the weekly meetings, it’s preparing all of us.”

Seeing more and more students join the Zoom meetings each week has boosted her confidence. She now feels less scared that her team won’t do the best job they can.

“I’ve been meeting more of the newer students, and I’m happy I can see them face-to-face,” Gaona-Perez said. “Even though it’s over a camera, I can still kind of form that connection with them.”

Like Donnelly, Gaona-Perez is trying to figure out how to train newer students and keep them engaged. She’s already noticed a lack of participation, but also acknowledged that the school year hasn’t started yet and students have external responsibilities.

“A lot of them like myself — I am an older sibling, and I have to look after the house, and so we’re trying to kind of figure out ways to get more participation — from especially the newer staff,” Gaona-Perez said.

Some publications waded into uncharted territory to better serve their communities, requiring some students like Dana Richie, co-editor-in-chief of The Southerner, to start their roles months earlier than expected. The Southerner, which covers Atlanta’s Henry W. Grady High School, ordinarily pauses news coverage over the summer, but they continued reporting this year because so many major decisions that impacted their community were made in the last few months.

Richie, 17, and her team covered initial school closure announcements, Black Lives Matter protests, and calls to rename Grady High School, over journalist Henry W. Grady’s explicit call to maintain “the supremacy of the white race in the South.” For Richie, it was important because she sees school newspapers as a way to get students’ voices out during an unsettling time.

“During those protests, the Black Lives Matter protests, we organized student comments where any student could write their opinion and we would publish it,” Richie said. “And I think just having this sort of voice for the community, especially in a time where everyone seems so isolated, is just really integral.”

Richie said The Southerner is a well-oiled machine — but that doesn’t mean it isn’t facing its own logistical issues. The Southerner publishes both online and in print, and much of its funding comes from selling print subscriptions. Now that the pandemic has potentially jeopardized the possibility of creating physical publications, her team is trying to brainstorm alternate ways to fundraise.

The Southerner isn’t alone in facing operational challenges. Gaona-Perez and Donnelly said their respective newspapers can use Google Drive to organize online content, but losing access to Adobe InDesign and Photoshop on school computers makes their print issues a larger obstacle to tackle.

But what might be the most frustrating part for these journalists is coming to terms with the fact that this was not the triumphant senior year they signed up for. The ODYSSEY hosts a banquet at the end of the academic year to present both in-house and conference awards to staff members, to hear speeches from outgoing leadership, and to ceremonially pass the reins to the incoming editors-in-chief — a tradition that Donnelly had been looking forward to.

“That’s kind of just when it hit me, when I realized we weren’t going to be able to do the banquet and introduce ourselves,” Donnelly said. “I’m not gonna get to have the same experience at all.”

Richie said she’s come to accept that this year will not be what she anticipated. She said she’s choosing to look at the silver lining of being editor-in-chief during this time because she feels that it will allow her to help younger students who need extra guidance.

“We’re still going to keep operating, even if we can’t do a print publication, and I think we’re going to have to learn new skills,” Richie said. “I’m really happy to help sort of lead that charge and lead that journey for the rest of the people in the publication.”

Photo of Blueprints Magazine Staff, as well as Broadcast and yearbook staff, at the Southern Interscholastic Press Association Convention in Columbia, S.C. on March 7. Photo courtesy of Blueprints Magazine.

For Gaona-Perez, the pandemic shed light on just how impactful Blueprints’ work is. She said she didn’t realize how many people read their news, and that they need to publish more. Cedar Shoals is going through a number of changes, from a new principal to uncertainty about whether students can return later in the semester, and Gaona-Perez said that the school needs reporters to keep people informed.

“It’s important to keep publishing because news is still going on,” Gaona-Perez said. “New things are happening every day in not just our school, but in our entire state. Our students, our teachers, the county need a form of news.”

Just a few months ago, twenty and thirty-something Brooklynites would crowd into Jupiter Disco, a hip, sci-fi themed bar on the edge of Bushwick on any given Friday and Saturday. There would be a packed bar, an electrifying dance floor, and an epic bathroom line. But these days, Jupiter Disco is almost completely empty.

Al Sotack, a co-owner of the bar, works alone, wiping the counters and worrying about his establishment’s future amidst the coronavirus pandemic. Sotack had to let all of his employees go so they could claim unemployment and was forced to close his doors to customers, transforming his once-bustling watering hole into a liquor store that provides drinks to New Yorkers in quarantine.

“You have millions of people just completely out of work with no real way to make any sort of income at all,” Sotack said in a video call with The Interlude. “There needs to be real support and I believe it needs to come from the state or we are completely fucked.”

Sotack isn’t alone. New York City bars, clubs, and liquor stores are struggling to adapt to the new economic and social realities while also trying to follow ever-changing guidance from the government. In March, the state shut down bars and restaurants (except for delivery and pickup) and legalized takeout alcoholic beverages. Outdoor dining became available in June, but was followed by the prohibition of outdoor drinking without food in July. However, following the guidelines presents tough challenges for the nightlife industry, as its appeal mainly comes from large crowds, open drinks, and loud conversations.

The restrictions the pandemic has brought have made the already tough nature of running bars, clubs, or liquor stores even harder. New York’s 2,100 bars account for about 5% of its nightlife industry, supporting 13,400 jobs, generating $492 million in wages and $2 billion in economic output, according to a recent report conducted by the Office of Nightlife. The same report revealed that 40% of business owners (restaurant, bar and dance clubs) were “either unsure or indicated that their businesses would not be open in three years.” Additionally, 47% of owners reported “a decrease in profit over the same period, with 17% experiencing a decrease that exceeded 10%.” To summarize, it is a challenging line of work.

“It seems there are a lot of life or death moments in the course of a successful bar’s lifetime and obviously most bars fail,” Sotack said. “Pretty much from the time you open, it really has to be a labor of love or why do it? From the time you open, it is a constant struggle.”

Sotack, who had been bartending two times a week, is now operating the bar single-handedly with his business partner and friend Maks Pazuniak. The only interaction he has with customers is when he walks to the door, masks and gloves on, to give them their to-go liquor order before retreating back to Jupiter.

“The bar was sustainable and then all of a sudden you cannot function at all,” he said.“Everything is on hiatus. I have no clue what will happen next. I think it is a pretty weird experience than just the day-to-day focus on growth and improvement.”

Sotack always wanted to open a bar and finally made it a reality in 2013 after teaming up with Pazuniak. Sotack used to be a freelance writer, but in the last couple of months, the bar had been his only source of income.

“There is also nothing to do here,” Sotack said, laughing. “Selling our liquor was just us liquidating our inventory because we have no way to pay. We are done. We have nothing right now.”

With the closure of nightlife operations, many vendors, alcohol distributors and DJs have also found themselves jobless. Gabriel Levy, one of the owners and operators of Rumpus Room on the Lower East Side, had to lay off his employees like Sotack.

“I feel for my employees and my contractors and for the vendors that we work with,” he said in a Zoom interview with The Interlude. “If you think about it, no business is an island.”

Photo illustration by Téa Kvetenadze

Rumpus Room has been closed since March, after trying to safely stay open as long as possible. Since Rumpus Room is a club, not a bar with food availability, takeout, delivery, and outdoor dining/drinking were not viable options. Starting in late February, Levy and his partners started reviewing incoming government policies and trying to revise their own health guidelines. At the beginning, this meant the bartenders wearing masks and gloves, deep cleaning the bar before and during the night, and not letting anyone who appeared to be sick in.

But by the first weekend of March, Levy had already noticed business was slowing, with an increase of cancellations from concerned customers. By the second weekend of March, they were “completely dead.” Levy said the club relies on advance bookings for business, which all but halted as soon as coronavirus cases began to spike in NYC.

“We are a small company that lives very leanly, we live pretty much hand to mouth,” Levy said. “We need to operate in order to be able to pay our expenses.”

While Levy supported Cuomo’s decision to close down, he was disappointed with the few steps taken to help small business owners.

One of these steps was Congress passing the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The law, signed on March 27, was “intended to assist business owners with whatever needs they have right now,” according to the NYSRA website. A part of the CARES Act is the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) which provides loans to help businesses keep their workforce employed during the pandemic. Business owners can have the loan forgiven if they use only 40% of the loan to pay for business costs such as rent, insurance, and utilities and use the rest towards the payroll of their employees. If they choose not to follow this rule, they have to pay back the loan.

Rumpus Room was given $50,000, however, Levy’s employees found that the unemployment benefits were more lucrative than being on payroll with the PPP. Like many small businesses, Rumpus Room had not been paying their $25,000 rent in full. Levy is worried about what landlords are going to do once the benefits for commercial tenants expire.

“In the absence of working with businesses, we are going to see New York City return to the ’80s when there were just tons of vacancies and nobody wants that,” he said. “The financial support mechanism of the crisis has been completely blundered by the government.”

“People don’t think of us as a place where you would sit outside, it’s a place where you would come inside and dance,” he said. “The larger question is how will the overall industry, the nightlife and hospitality industry, survive this in the absence of the government stepping up to support the businesses as well as the employees?

Unlike Sotack and Levy, Jean Baptiste Humbert, owner of Wine Therapy, has been satisfied with how his business has been doing.

Humbert has hardly ever shut down his small wine shop since its opening in 2005. When Hurricane Sandy hit New York and wiped out half of the city’s electricity in 2012, he kept the store open by candlelight. He couldn’t ring transactions so he would write down people’s names and numbers on notepads to charge later. While seasoned in crisis management, Humbert has never experienced anything like COVID-19.

“It is a very strange situation,” he said during an interview with The Interlude over Zoom. “I never lived [through] anything like that.”

The pandemic has forced him to slash hours and customers now wait outside for wine instead of walking around the small store. People can also place an order or call before coming to pick up. Humbert said that, contrary to the situation for many bars, his business has been doing well. They even increased their inventory by $10,000 because there is more demand for alcohol.

“Some Saturdays it’s busier than I have ever seen — it is pretty crazy,” he said.

People all around the U.S. have been consuming more alcohol. In the week ending March 21, according to market research done by Nielsen shared by the Associated Press, the sale of alcoholic beverages across the country rose 55%. Tequila, gin and pre-mixed cocktail sales have gone up 75%, while wine sales are up 66% compared to last year.

While some businesses are suffering and others are persisting, the uncertainty the future holds is the same for all; whether that is the decline of purchasing power, eviction scares, or running out of inventory. The changes in policy and rules regarding nightlife make it difficult to survive in an already difficult industry that relies on in-person, social interactions.

“I think this is unprecedented,” Sotack said. “Certainly prohibition was a distinct experience and obviously left its mark in a very significant way, you know I could not hazard a guess as to the cultural changes that will be the result of this.”

Former Glossier retail employees have taken to social media this week to call out the famed makeup brand for creating an unsupportive work environment, especially for workers of color, via Medium, Twitter, and Instagram.

The accounts, called Outta the Gloss (a reference to a popular Glossier blog Into the Gloss), were created by the makeup brand’s former retail employees. The posts, which were released about a week after the company laid off all of its retail staff, recount several ways in which the company failed to protect and support its retail workers, especially workers of color.

“Many of us were duped by the pink brand from Instagram,” the one post reads, “[The flagship leadership was] ill-equipped to guide a diverse team through the unique stressors of working in an experiential store and assisting customers who are often justifiably frustrated by the disorienting flagship model.”

Glossier CEO Emily Weiss wrote last year: “The tens of thousands of people who visit our two stores weekly aren’t just coming for products they could buy online — they’re lining up for the community and the experience of being together.” Yet, the Outta the Gloss’ lengthy post recounts a number of ways in which the company failed to create said supportive environments for its retail workers, or “offline editors” as the brand calls them.

The editors behind the account provided several examples of microaggressions, sexism, and racism the workers had to endure, which they allege were not addressed and handled by management or HR. The incidents included allowing a woman who visited the store to repeatedly refer to the company’s Latinx workers as “illegals” into the store; permitting a group of chaperoned white teens to wear the darkest Glossier makeup shades, emulating blackface; not reprimanding a manager who randomly confused the names of their BIPOC workers and was not fired for it, despite numerous requests and not reproaching a man who proceeded to massage an editor without her consent.

The store, according to the former retail workers, employed a “surprise and delight” marketing strategy which ensured customer satisfaction often at the expense of employees’ wellbeing. Customer complaints, even if accompanied by aggressive and disrespectful behavior, were met with gifts and full refunds. The workers allege their complaints fell to the wayside. And while the editors admit that retail and customer service work may require one to make some personal sacrifices to begin with, “the idea that sale supersedes humanity and dignity of an employee is abhorrent no matter where one works.”

Glossier has now joined a growing list of millennial companies — like Everlane, Away and Reformation — whose self-propagated online image of diversity and inclusion is not held up behind closed doors. Management allegedly implied to the editors that due to the popularity of the brand, both as a workplace and a shopping destination, those that did not wish to work there anymore or voiced too many concerns could easily be replaced. “Former editors exasperated with the company’s inability to adhere to its own published values have often sounded a death knell upon quitting, advocating for those still working at the store” the post reads, “but they leave knowing that there’s a young fan who, as long as they keep “cool” and are affable, will soon replace them and make fewer demands.”

In addition to leadership’s inability to manage and prevent its workers’ emotional turmoil, the makeup brand failed to facilitate safe working conditions, as well. The posts recollect the lack of air conditioning in the showroom during humid NYC summers as well as the habitual violations of penthouse occupancy limits (the maximum capacity for the Glossier Lafayette Street showroom was 16 people according to NYC Department of Buildings documents obtained by The Interlude; the sales team alone exceeded that number). Outta the Gloss posts also describe how there were no break rooms, which forced the staff to eat and rest on the “damp room’s floor riddled with rat waste,” and more. The former employees allege that they were told the conditions would improve once the company grew.

View this post on Instagram

The former employees laid out several demands of Glossier, which includes an open Zoom call where the makeup brand will commit to equalizing and elevating BIPOC editor voices, quarterly company-wide anti racism training, transparency regarding wages, pay parity and more.

“We know the proclaimed brand values of inclusivity, accessibility and equity should apply to us,” the posts conclude, “We ask Glossier’s devoted community: if [the brand’s vow to democratize beauty] is only achieved by pernicious silencing of Black and Brown editors and without treating marginalized staff equitably — have they democratized beauty at all, or is it more of the same?”

A representative for Glossier told The Interlude via email that the company initiated conversations with its retail team members about where it had fallen short in June, and said the company quickly moved to “investigate their claims with guidance from outside counsel, and in early July, shared an initial action plan based on their feedback and the findings from the investigation.” The Interlude has not been able to confirm whether such a discussion occurred.

Outta the Gloss did not immediately respond to The Interlude’s requests for comment.

We will update this story as it develops. Additional reporting by Cameron Oakes

After a trip from Cuba when she was a college freshman, Fatima Julien traded her dad a box of cigars for her first camera: a Canon Rebel T6. She said he may have realized it was an unfair bargain later on but that she’d never return the camera.

“I don’t know how that worked out, it was the best gamble of my life,” said Julien, 21. “So I just randomly started taking pictures because I got a camera. It was great. I still take pictures on that same camera.”

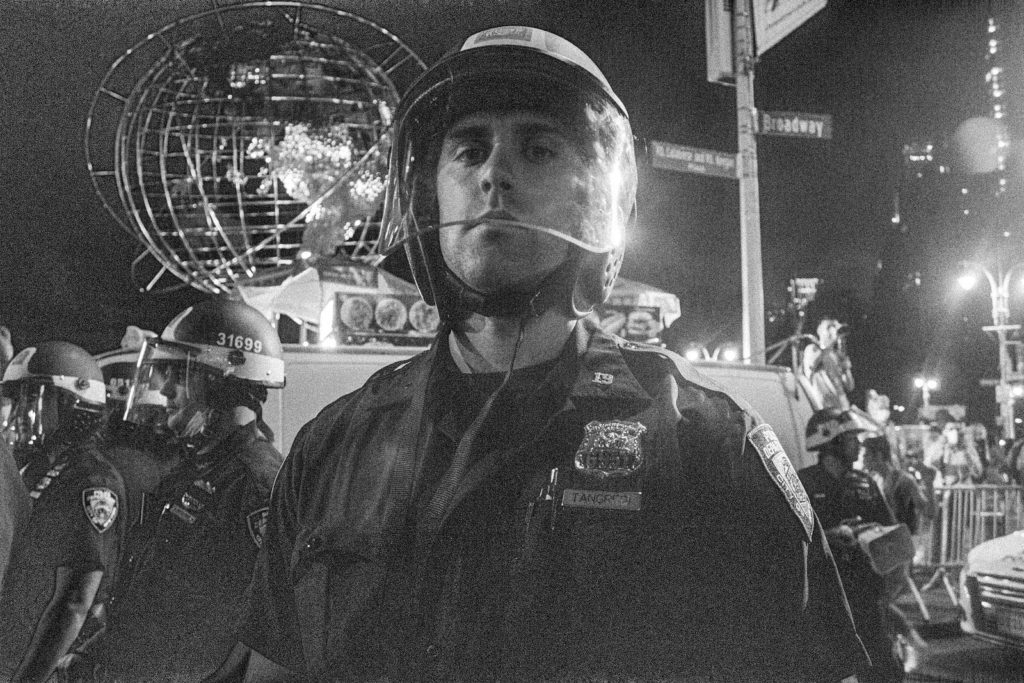

Julien’s art is not just limited to photography — she is also a filmmaker and writer who hopes to create a platform for Caribbean storytellers in the future. Her latest project, Portrait of Pigs, documents the police that lined the New York streets during the recent wave of Black Lives Matter protests that have been sweeping the nation. Julien, who was born and raised in Haiti, spent pockets of time in the United States as a child, where she was introduced to the idea of police presence in everyday life.

“My aunt used to scare us into being good kids by telling us about po-pos, so I had made them to be these monsters in my head,” she said. “So the first time I got pulled over by a cop, I literally started bawling my eyes out, and he was not very nice about it.”

Photo by Fatima Julien.

She graduated from New York University in the spring with an Individualized Degree in Media Studies and International Law, where she studied how media portrayals of race impact international relations and laws. The black and white photo series evokes the emotional turmoil that has existed between Black communities and the police since before the abolition of slavery. By making her subject the police instead of protesters, Julien sees Portraits of Pigs as a way to invert the power dynamics of surveillance that often play out in protest photography.

The Interlude spoke with Julien via Zoom recently about her project and how it was therapeutic for her as a photographer concerned with media ethics and the safety of Black protesters in the age of Black Lives Matter. The following interview has been condensed for clarity.

How did you come up with the Portraits of Pigs photo series?

I am on the shyer end of things. I feel like a lot of photographers can just go out and take pictures of people, but it stresses me out to do that because I don’t know if this person wants me to take their picture, especially if that person looks at me, then I’m like, “Is that okay?” It’s very awkward for me doing protest photography. In a way, it helps for me to get out of my comfort zone and forces me to talk to people and interact with people. But with something as sensitive as the protests for Black Lives Matter, I knew that there were so many emotions there and I just didn’t feel right taking away somebody’s agency like that or getting in somebody’s face with a camera and taking their picture, like it just felt awkward, and wrong, and difficult. So then the easiest thing for me to do is to take pictures of the cops.

In previous protests, cops had used [protest] photographs to track down protesters and leaders in the Black Lives Matter movement and try to harm them, that pissed me off. So I was like, you know what, how about I flip the script in a way? And as opposed to taking people’s pictures I could take the cops’ pictures, that way I’m not taking away somebody’s agency, I am taking away [the cops’] agency. In so many instances it’s been the opposite, with cops taking away the agencies of Black people. I’m angry. They’ve taken so much from people that look like me. They’ve taken so much from me, so I just wanted to do something that shows that. Photography is a very weird art form because of the different power dynamics that come with it.

Was there any specific intention behind making every photograph black and white?

Black and white photography is just the way I shoot. I think shooting with color is beautiful, I just personally don’t enjoy it. There’s a truth to black and white photography that I haven’t been able to find with color photography in terms of my own personal work. It forces you to focus on the subject. I like the directness.

Photo by Fatima Julien.

Is there a future for this photo series?

I have so many more [photos] but I was like, I’m tired of spamming Instagram. It felt weird posting them all with everything going on. I didn’t want it to become about me, per se, because I found myself refreshing, checking to see how many likes they got. I think for now I am not going to post my pictures, but instead I will repost the pictures, for example, of the cops who murdered Breonna Taylor. I think the whole point is, as opposed to having Black people’s faces splattered everywhere potentially putting us in danger, I rather it be the other way around, like we splatter their faces around, and we show who the bad guys are. A lot of times history forgets to immortalize the bad guys. We do immortalize the good guys but that also places us in a spot of vulnerability.

Why did you start creating art?

I think photography, specifically, it was mostly anxiety. Because my anxiety is so crazy, it’s all about figuring out ways to have control over my environment, that way I don’t feel like I am going insane all the time. So basically my photography was a way to kinda like take a picture, and then spending time and editing it. It was a way of calming down. It was soothing. It was more like me having agency over the things around me as opposed to the things around me having agency over me. I started taking pictures because of that.

How would you describe your artistic process?

So many accidents. I have an ongoing text message chain with myself where I will just wake up in the middle of the night and be like, “Oh, this is an idea I have,” like a movie idea or something that I want to write and I will just text it to myself. They’ll come to me in dreams. A lot of my academic pursuits also informed what I want to be doing. For my thesis, I was writing about Haitian Loas and Haitian Spirits and just how Haitian Voodoo worked. And a lot of my subsequent ideas in filmmaking and so on were informed by that. I do want it to be a bit more intentional I think. That is what I tried to focus on with the series Portraits of Pigs, I was trying to make it as intentional as possible.

Photo by Fatima Julien.

What role does art play in the revolution?

If we consider writing and all that other stuff art, like a lot of that has historically been written by white people. It has been written about us. It has been written about the oppressed. Pictures have been drawn of the oppressed. The Hatian Revolution, I think a lot of the paintings we have of it were drawn or painted by white people, which is mad weird because this was one of the instances where we were the victors, and that’s something that I never could wrap my head around. In terms of having agency over yourself, having agency over your body which is a very big part of the revolution; art plays a huge role in that sense.

We have to create our own narratives and we have to rebel against the narratives that were written for us. If everything is as a result of narrative, then we have to be able to take those narratives back and change them, or reimagine them in order for us to be able to move forward. With everyone being like, ‘But what are we going to do in the future? What’s going to happen when we do abolish the police?” You can’t necessarily imagine another world if you’re still stuck in it. So we need people that are actively re-imagining worlds. We need people that are actively working on destroying this world with their art. We need people that are actively contributing to alternate narratives as opposed to focusing on whatever [narratives] have been circulating now for centuries.

The outbreak of COVID-19 in the United States wreaked havoc on minority communities, causing long-existing systems of racism and oppression to permeate deeper into the lives of the country’s most vulnerable. As it transformed New York into a global hotspot for the disease, the virus caused the city’s growing food insecurity problem to get even worse. The pandemic exposed how significantly disproportionate the problem is for low-wage and minority communities, increasing the number of New Yorkers left without access to affordable, healthy food from around one million to more than two.

In an effort to diminish the impact of the issue, local activists and community organizers took action by installing community fridges in neighborhoods across the city. By offering fresh produce, prepared meals, and pantry staples that are free to all, the fridges have become an increasingly popular mutual aid effort to combat food insecurity and food waste.

Sara Allen, a volunteer with The Friendly Fridge BX was inspired when they saw a friend’s Instagram post about the first community fridge in Manhattan. Just three days later, they had a fridge up and running in their own neighborhood. “Regular folks can do it,” Allen told The Interlude.

But where should you start?

After speaking with several organizers from neighborhoods across the city, The Interlude has put together the following guide to starting your own community fridge.

Do Your Research

First, you should familiarize yourself with the core concepts that make community fridges effective. Read up on the ideas behind mutual aid systems, a community-centered method of direct action that encourages individuals to care for each other and work together to address their community’s most pressing needs. Think about how to promote solidarity rather than charity. In efforts of solidarity, unlike in charity, the savior complex is eliminated. There is no one in charge and no policing of how people choose to engage. Everyone can give and everyone can take.

“There’s a lot of pride, shame, and guilt [associated with] anything that is given away for free,” explained Sade, an activist, artist, and volunteer with The Harlem Community Fridge. “People become a little suspicious — ‘Is it good enough?’ Or there are other attachments, like if you accept something that’s free, that means that you’re poor…[s]o there’s a lot of stigma and preconceived, indoctrinated ideas that we as a society have to work through.”

Developing a foundational understanding of these ideas is necessary to building an effective mutual aid program, such as a community fridge.

Connect With Other Organizers

Most community fridge organizers are very active on social media, especially Instagram (All of the organizers that The Interlude spoke with for this guide were contacted via Instagram.) They make themselves available to answer questions or help connect interested volunteers with resources. Sg Guerrero, an organizer who helped start The Uptown Fridge in Washington Heights, initially saw an Instagram post from the activism network In Our Hearts NYC that was offering a free fridge. IOH provided Guerrero with the fridge and even coordinated a group chat with other Washington Heights residents looking to start a community fridge. IOH encourages anyone interested in starting a community fridge to message their Instagram account or send an email to inourhearts@gmail.com. Other networks, like FREEdge, offer resources like micro-grants, templates for informational flyers and posters, and a comprehensive guide to understanding and building community fridges.

Photo by Opheli Garcia Lawler.

Take Care of the Logistics

After you’ve reached out to other organizers and volunteers to start building a team, it’s time to focus on the logistics — how will volunteers communicate? Where can the fridge be plugged in? When will the fridge be cleaned and restocked? Most organizers recommend starting a group chat on a messaging platform like Signal so that team members can easily contact each other and share information.

Then it’s time to find an outlet for the fridge. The majority of fridges in New York are plugged in at a small local business like a deli or a bodega. While looking for an outlet for The Friendly Fridge BX, Sara and their partner Selma Raven simply walked up and down the block introducing themselves to business owners and asking for their help providing electricity. Some people will be very skeptical and unwilling, they both warned. But just keep trying and you’ll find someone who is excited to be involved. Extension cords will be necessary, but make sure everything is connected safely. Don’t plug an extension cord into another extension cord, and make sure the outlet is not being used to power other appliances.

Once the fridge is plugged in, allow 24 hours for it to cool before stocking with food. All food in the fridge should be clearly labeled with expiration dates and regular cleaning of the fridge should be coordinated by team members. Aditi Varshneya, another organizer with The Uptown Fridge, suggests starting with a Google Spreadsheet that displays who can take care of specific duties on what dates and times. It’s also important to appoint one or two people to oversee monetary donations, which community members typically contribute via Venmo. Lastly, make your fridge visible. Use bright colors and encouraging messages to communicate to anyone passing by that the food inside is free and available to everyone.

Involve Your Community

The inclusion of the whole community is the most important step to a successful fridge. Make connections with bakeries, grocery stores, restaurants, corner stores, and food pantries in the area and offer to coordinate regular pick up times to collect donations. You can also ask these businesses to put up posters with information about the fridge. But always keep in mind that no donation is too small. Encourage friends and neighbors to drop off that stray can of beans they don’t need or check for buy-one-get-one deals at the grocery store and donate the extra item.

“We can all do something. Everybody can contribute,” Sade told The Interlude. “It’s not just for businesses with money. Maybe one day you’re leaving something and the next day you come and pick something up. There’s no questions asked.”

Commit to Doing the Work

Community fridges are about more than feeding the hungry. The fridges fight issues deeply ingrained into American society, like food insecurity, food waste, and food apartheid — the systemic inaccessibility of affordable, healthy food options that disproportionately affects black and brown communities. Anyone who’s thinking about starting a community fridge in their neighborhood should consider these issues and be ready to commit to long-term activism in the form of re-educating one’s community about our country’s food systems.

“[We’re addressing] health disparities, accessibility of healthy food options, and offering people better ways to eat,” Sade said. “When you do this kind of work, you’re really helping to mend and build bridges. Food is the connector between all people.”

Brittany Talissa King, an activist and reporter, was the angriest she had ever been after seeing the back-to-back murders of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile by the hands of police less than 48 hours apart.

“When I saw that, something in me snapped,” she said. King said that up until that point in her life she never felt such intense rage take over her body.

On July 7, 2016, she launched the Black Lives Matter chapter of Columbus, Indiana, which she spearheaded for two years. Her experience as an activist and love of writing inspired her to follow her dreams to New York City, which meant formally ending Black Lives Matter of Columbus (BLMC) and beginning a new chapter of her life as a cultural critic and reporter. After graduating from NYU’s Graduate Journalism program, King, now 31, has taken to freelance journalism. In her prose, King channels her energy towards the issues she cares about. Her latest piece, “I Am Not Your #HashTag” critically examines the performative nature of white allyship.

The power that fueled King’s prose led her to study at Indiana University majoring in Writing and minoring in Literature in 2012. IU is also where her roots in activism began, staging a die-in at her alma mater a week after NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo killed Eric Garner on July 17, 2014. She graduated that same year. Her writing career continued to grow after earning her Bachelor’s, picking up writing gigs after her undergraduate studies. Two years after the die-in, King organized a pivotal protest at Columbus’ City Hall after seeing the deaths of Castile and Sterling on camera pushed her to a breaking point.

“I was like, ‘I need to get this out in a more positive way,’ so I decided to protest at the City Hall building in Columbus,” King said. “I texted like 15 of my friends. They came. We protested for like three hours.”

On July 6, 2016 in front of the City Hall building, King and her friends were both welcomed and rejected by those in the community who watched their demonstration. While protesting, King realized that Columbus — the town she and Vice President Mike Pence both called home — was in desperate need of a change.

The 2016 Indiana Presidential elections saw 63% of voters in Bartholomew County cast their ballot for Trump. During the last election cycle, Pence said there was “too much of this talk of institutional bias or racism within law enforcement,” and in June of this year, called the Black Lives Matter movement “a political agenda of the radical left” on CBS News. Still, in the midst of a harsh political climate, that protest catalyzed the King’s founding of the first #BlackLivesMatter chapter in Columbus on July 7, 2016, at a time where polls showed roughly four-in-ten Americans supported the Black Lives Matter movement according to the Pew Research Center.

“I was talking to my friend Jessarae [Emberton], and I was like, I’m sick of protesting,” King said. “I’m sick of the fact that I can use this exact poster for the next time a Black person dies.”

“She created this core council of people,” said Jessarae Emberton, who has known King for more than 10 years and helped her launch the chapter. “We just started holding monthly meetings, having conversations, and Brittany [King] would come up with ideas for these events.”

King said she was unapologetic in the formation of the chapter, insisting it be called Black Lives Matter despite backlash against the name. Yet, a steady stream of around 15 to 50 people would attend their meetings on racial relations and issues according to Emberton. One hundred and fifty people attended the chapter’s first MLK Jr. Day event in 2017, “Reclaiming the Legacy of Dr. King Jr.

All of these milestones were reached within a year, and not over the span of five years like which King predicted. She was shocked. Despite this showing of public support, King said she also experienced great resistance to the movement, including death threats from white supremacists’ groups in 2017.

“One leader of one group doxxed me, which he put my address and number and all my information on the internet,” King said. “Then a month or two later, a white supremacist direct messaged me and then posted on the #BlackLivesMatter Facebook page ‘Black lives don’t matter, lynch yourself you n****r.’ He had a picture of me being drawn into a warehouse and then lynched.”

This experience traumatized King, but she continued to lead the chapter, believing in what BLMC was trying to accomplish. A more substantial support network continued to emerge for King and her chapter. She was offered the role of keynote speaker at the 21st annual Martin Luther King Jr. Community Breakfast in 2018, a significant event in her city, where she talked about the whitewashing of MLK Jr.’s nonviolent legacy.

“I am defiantly passionate about this country, only because of what I’ve learned about my heritage,” King said. “They strived so hard to make sure they had a place in the country they built and so in a way I find myself doing that on their behalf.”

She noticed that after the local BLM chapter was established, many other Black organizations, like the local chapter of the NAACP, African American Fund, and the African-American Pastor Alliance (AAPA) became more outspoken on the racism that existed in the city. The president of Bartholomew County NAACP told The Republic in 2018 that BLMC was, “a very powerful young group” and AAPA’s leader said that the chapter, “provided a voice for the community as it related to African Americans.”

“We kind of were the organization to be sacrificial lamb for the Black people, to be like, we’ll take the first hit, we’ll take the biggest one and then now you guys can speak up,” King said.Photo illustration by Josh Magpantay.

After an almost three year run, BLMC disbanded as the chapter could not find a successor for King’s leadership after she departed for NYU’s Graduate Studies in Cultural Reporting and Criticism (CRC) in the fall of 2018. King’s enrollment at NYU marked her transition from marching in the streets to being “a critical thought activist.”

“There was no one else in the community that wanted to step up and do that labor of love,” Emberton said of BLMC’s end.

King’s personal journey with founding and then leaving BLMC allowed her to re-center her love of writing after she was put in the crosshairs of local media outlets.

“Seeing how the media manipulates the world to hate us, I mean I knew that, but really being in the center of it locally, and then seeing it nationally and globally,” she said. “I was like okay, I really need to transition this activism to where I am at the table and where I can try to stop some of these stories from being published, and put in a Black voice for our community in the media.”

While at NYU, King was the only Black person in her academic cohort of 10 in the Cultural Reporting and Criticism program, and found herself oftentimes being the only voice that spoke up for the Black perspective and experience in every facet of her program. Her pent-up frustration stemmed from a lifetime of always being the only Black person in the room, coming from a town where over 47,000 people, a little over 1,000 were Black. King did not expect to see the same demographics for the classrooms of NYU.