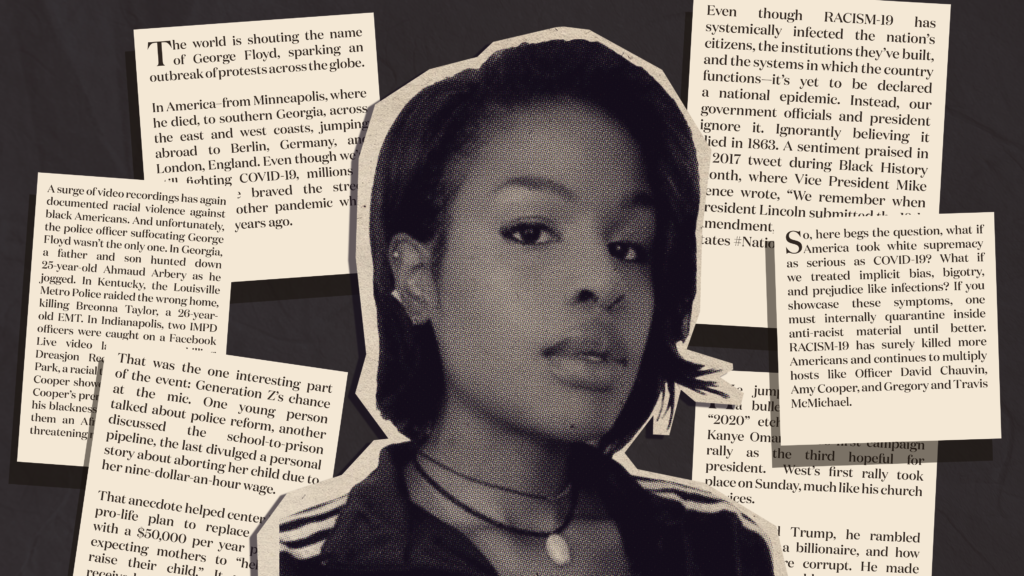

Meet Brittany King, Black Activist and Journalist

She describes her activism as “staying defiant in all mediums.”

Brittany Talissa King, an activist and reporter, was the angriest she had ever been after seeing the back-to-back murders of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile by the hands of police less than 48 hours apart.

“When I saw that, something in me snapped,” she said. King said that up until that point in her life she never felt such intense rage take over her body.

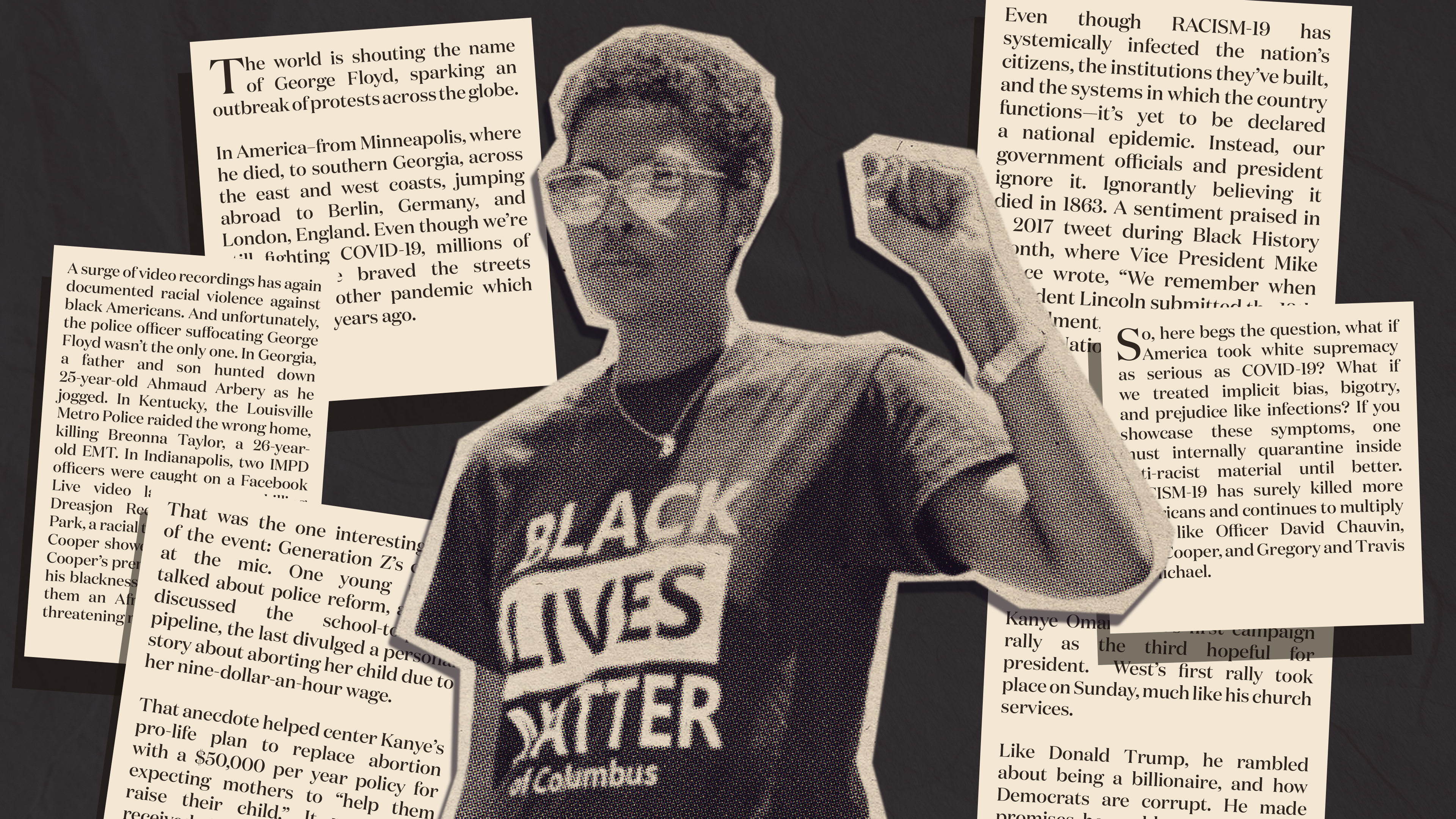

On July 7, 2016, she launched the Black Lives Matter chapter of Columbus, Indiana, which she spearheaded for two years. Her experience as an activist and love of writing inspired her to follow her dreams to New York City, which meant formally ending Black Lives Matter of Columbus (BLMC) and beginning a new chapter of her life as a cultural critic and reporter. After graduating from NYU’s Graduate Journalism program, King, now 31, has taken to freelance journalism. In her prose, King channels her energy towards the issues she cares about. Her latest piece, “I Am Not Your #HashTag” critically examines the performative nature of white allyship.

The power that fueled King’s prose led her to study at Indiana University majoring in Writing and minoring in Literature in 2012. IU is also where her roots in activism began, staging a die-in at her alma mater a week after NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo killed Eric Garner on July 17, 2014. She graduated that same year. Her writing career continued to grow after earning her Bachelor’s, picking up writing gigs after her undergraduate studies. Two years after the die-in, King organized a pivotal protest at Columbus’ City Hall after seeing the deaths of Castile and Sterling on camera pushed her to a breaking point.

“I was like, ‘I need to get this out in a more positive way,’ so I decided to protest at the City Hall building in Columbus,” King said. “I texted like 15 of my friends. They came. We protested for like three hours.”

On July 6, 2016 in front of the City Hall building, King and her friends were both welcomed and rejected by those in the community who watched their demonstration. While protesting, King realized that Columbus — the town she and Vice President Mike Pence both called home — was in desperate need of a change.

The 2016 Indiana Presidential elections saw 63% of voters in Bartholomew County cast their ballot for Trump. During the last election cycle, Pence said there was “too much of this talk of institutional bias or racism within law enforcement,” and in June of this year, called the Black Lives Matter movement “a political agenda of the radical left” on CBS News. Still, in the midst of a harsh political climate, that protest catalyzed the King’s founding of the first #BlackLivesMatter chapter in Columbus on July 7, 2016, at a time where polls showed roughly four-in-ten Americans supported the Black Lives Matter movement according to the Pew Research Center.

“I was talking to my friend Jessarae [Emberton], and I was like, I’m sick of protesting,” King said. “I’m sick of the fact that I can use this exact poster for the next time a Black person dies.”

“She created this core council of people,” said Jessarae Emberton, who has known King for more than 10 years and helped her launch the chapter. “We just started holding monthly meetings, having conversations, and Brittany [King] would come up with ideas for these events.”

King said she was unapologetic in the formation of the chapter, insisting it be called Black Lives Matter despite backlash against the name. Yet, a steady stream of around 15 to 50 people would attend their meetings on racial relations and issues according to Emberton. One hundred and fifty people attended the chapter’s first MLK Jr. Day event in 2017, “Reclaiming the Legacy of Dr. King Jr.

All of these milestones were reached within a year, and not over the span of five years like which King predicted. She was shocked. Despite this showing of public support, King said she also experienced great resistance to the movement, including death threats from white supremacists’ groups in 2017.

“One leader of one group doxxed me, which he put my address and number and all my information on the internet,” King said. “Then a month or two later, a white supremacist direct messaged me and then posted on the #BlackLivesMatter Facebook page ‘Black lives don’t matter, lynch yourself you n****r.’ He had a picture of me being drawn into a warehouse and then lynched.”

This experience traumatized King, but she continued to lead the chapter, believing in what BLMC was trying to accomplish. A more substantial support network continued to emerge for King and her chapter. She was offered the role of keynote speaker at the 21st annual Martin Luther King Jr. Community Breakfast in 2018, a significant event in her city, where she talked about the whitewashing of MLK Jr.’s nonviolent legacy.

“I am defiantly passionate about this country, only because of what I’ve learned about my heritage,” King said. “They strived so hard to make sure they had a place in the country they built and so in a way I find myself doing that on their behalf.”

She noticed that after the local BLM chapter was established, many other Black organizations, like the local chapter of the NAACP, African American Fund, and the African-American Pastor Alliance (AAPA) became more outspoken on the racism that existed in the city. The president of Bartholomew County NAACP told The Republic in 2018 that BLMC was, “a very powerful young group” and AAPA’s leader said that the chapter, “provided a voice for the community as it related to African Americans.”

“We kind of were the organization to be sacrificial lamb for the Black people, to be like, we’ll take the first hit, we’ll take the biggest one and then now you guys can speak up,” King said.Photo illustration by Josh Magpantay.

After an almost three year run, BLMC disbanded as the chapter could not find a successor for King’s leadership after she departed for NYU’s Graduate Studies in Cultural Reporting and Criticism (CRC) in the fall of 2018. King’s enrollment at NYU marked her transition from marching in the streets to being “a critical thought activist.”

“There was no one else in the community that wanted to step up and do that labor of love,” Emberton said of BLMC’s end.

King’s personal journey with founding and then leaving BLMC allowed her to re-center her love of writing after she was put in the crosshairs of local media outlets.

“Seeing how the media manipulates the world to hate us, I mean I knew that, but really being in the center of it locally, and then seeing it nationally and globally,” she said. “I was like okay, I really need to transition this activism to where I am at the table and where I can try to stop some of these stories from being published, and put in a Black voice for our community in the media.”

While at NYU, King was the only Black person in her academic cohort of 10 in the Cultural Reporting and Criticism program, and found herself oftentimes being the only voice that spoke up for the Black perspective and experience in every facet of her program. Her pent-up frustration stemmed from a lifetime of always being the only Black person in the room, coming from a town where over 47,000 people, a little over 1,000 were Black. King did not expect to see the same demographics for the classrooms of NYU.

“My presence in a way was activism, exhausting though, so exhausting,” she said. “Sometimes I go home and cry…because I was thinking, some of these people are journalists, not some, all of them are journalists,” she said, referring to her fellow writers in the cohort. “They’re going to go out into the world and they have no idea how harmful some of the things that they’re saying are going to influence people.”

Jda Gayle, 30, met King when she visited NYU as a prospective student before enrolling in the CRC program in September 2019. Gayle said that King was invaluable in learning how to navigate the graduate journalism school as a Black student, with her most memorable moments with King being their conversations on race, and how to write about it in a thought-provoking way. Gayle was one out of two Black people in the CRC cohort of twelve in the class below King’s.

“When I arrived on campus for the first day of orientation, I was very disappointed that the class was so white,” said Gayle citing the need for different perspectives in a Cultural Reporting and Criticism program. “America is never lacking in the perspectives of white people, it’s just not a thing that is ever going to run out in this country. For me to come to a program basically at 30 years old and to see that I am in an environment with a bunch of wealthy, early 20s white people, it’s just kinda like, well damn.”

This frustration was also shared by Kayla Stewart, 28, was one out of two Black people in NYU’s Global Journalism cohort of 17. She met King in Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Writing for Reporters class in spring 2019, where she appreciated King’s praise of a “deeply personal essay” she wrote that was the subject of debate among some classmates.

“I felt like there definitely could have been an effort on behalf of the journalism school to find more Black students, like, it’s New York City,” Stewart said. “It was a lot of pressure to kind of have to answer for a community that is so diverse, but [that] definitely happened.”

Despite the isolation King felt at NYU, having role models like Ida B. Wells got her through the emotional turmoil she endured as a Black activist and journalist. “If Ida can like, be writing about the lynchings, going to lynch mobs, reporting, and putting her life on the line for this profession,” said King, “I can put my tears on the line.”

King said that her time at NYU with top-tier journalists and writers made her realize not only the responsibility that comes with being a journalist, but the role she could play in creating prose that was accessible and directly speaking to her community. In one of the essays she wrote in Ta-Nehisi Coates’ reporting class, “Black Anger: How To Baldwin the United States,” she begins to process the numbing rage that pushed her to spearhead that City Hall protest years ago. An excerpt from King’s essay reads:

At our consumption, this love is a pill coated with calm and injected with resilience. Where our “blind fever” can be under our control to face the ailments of The Systems. However, when this pill is given to our oppressor, their ignorance malfunctions; their whiteness short-circuits; exposing their American immortality is actually a generational disorder. Where they succumb to understand their superiority survives on cannibalizing black identities and black hearts like beasts.

King’s activist work is completely embodied in her journalism career. King said she emphasizes the importance that writing has had in the history of slavery from “manipulating the Bible” to justify enslavement to scientific journals historically publishing false observations by white anthropologists to dehumanize Black people.

“Slaves would be killed if they were reading, writing, teaching each other how to write, touching a book, looking at a book, looking at script,” she said. “I find that me, reading and writing and doing journalism, against the very thing that took my ancestors is the most defiant thing I can do. My pen is my weapon now against white supremacy.”

Photo illustration of Brittany King by Josh Magpantay.

Now working as a freelance journalist, King described her activism as “staying defiant in all mediums.” The countless times she had to urge her former classmates to consider Black perspectives in their criticisms on universal topics, like hair or feminism, further drove her motivation to become a powerful critic in the media. The care she holds for journalism meant that she wanted to incite her overwhelmingly white field, where people of color make up only 18.8% of newsroom managers at both print/digital and online-only publications, to think of Black voices as being necessary to their work, not an afterthought.

“This is the world of what I am walking into,” King explained. “If you can’t stand up against one person in a cohort, then you aren’t going to stand up to the public after you graduate.”

Her interrogation of every sentence she writes is necessary to King, who describes her best writing as being straightforward and honest. She stands by her work and is proud of herself, especially after the semesters of hard conversations, critiques, and isolating experiences at NYU.

“I am proud that you did not buckle under pressure, and I am proud that you stayed protesting against racism even with prose. Not a picket sign, but with prose,” said King of herself. “You’re not going to do it in the streets, you’re not going to do it in writing either.”

She explained that Black voices in writing and journalism have always been an essential part of the resistance, and that more representation in media is a form of protest in itself. She considers it a critical point to rewriting a history that has never been kind to Black people. Her recent piece for The Republic, “Racism-19”, discusses the parallels of the COVID-19 with the effects of systemic racism, noting that Black people are suffering disproportionately from both (and it’s no coincidence). She also begged the question: if America could fight COVID-19, why not also implement policies “to flatten the curve” of anti-Blackness?

“We need Black people marching, we need Black people in law, we need Black in the government, we need Black people writing, painting, dancing,” King said. “We need it all to reach Black liberation.”

During the COVID-19 era of self-imposed quarantining, King said she takes advantage of the nation’s increased online presence and connectivity by observing how different groups of people are reacting to the news via social media platforms, which informs her writing topics. She believes her critical eye and penchant for thinking outside the box will be useful in the journalism she produces to further the dialogue on issues like #BLM and “and making something covert, overt.”

To keep her hopefulness afloat, though, King listens to old speeches by Black leaders and has a steady self-care routine which consists of a nice breakfast, writing, hour-long walks or runs in the afternoon and evening. Now, in her community, she wants to encourage young Black people in her community to realize their potential and invest in their future, a legacy of her educational work during BLMC’s span.

Her optimism anchors her future outlook for the movement, trusting, for example, that Black women will be more recognized not only as the founders of Black Lives Matter and organizers of many chapters nationally, but that more people demand justice for Black women murdered in unlawful police killings.

“Black women just need to get recognized in general, for their lives,” she said. “Also, when we die, it needs to be taken as seriously as when men die.”